The following was written by ELMS member Geoffrey Spencer, 2 Royal Hampshire Regiment. Captured by Rommel’s Africa Corps in North Africa and following incarceration in POW camps in Italy and Germany, and after many escape attempts, he eventually broke out from Stalag IV A at Dresden.

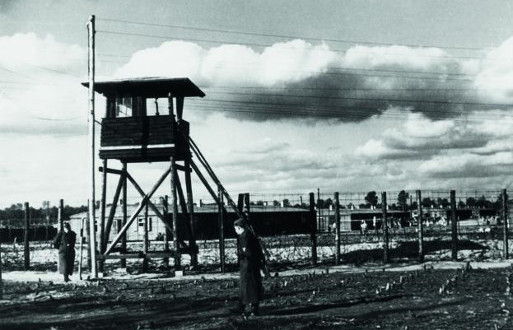

I, like thousands of others during our period of captivity, was constantly thinking and planning ways to escape. I had come to realise, especially after my futile attempts to escape in Italy, that although getting out of camp was by no means easy, and quite hazardous, getting home after the breakout was an even bigger problem. Getting out of a camp at first sight seemed to be impossible. The camps were surrounded by a double barbed wire fence attached to posts every few yards and topped with coiled barbed wire. Guard towers were situated at intervals and at about fifteen yards inside the fence, and a couple of feet above ground, was a trip wire. The area between the trip wire and the fence was no-man’s land and the guards had orders to shoot anyone trespassing into this area. Apart from the guards in the towers, other guards regularly patrolled around outside the main fences.

Security however depends very much on the constant alertness of the soldiers who, month after month, were doing what must have been a very boring job. Most of them had spent some years fighting in various campaigns and on the Russian front and were now, for various reasons, no longer fit for active service. Many of them were fed up with the war and were hoping that it would be over so that they could go back home. The behaviour of the guards was under constant scrutiny by would-be escapers. There were always some who were less conscientious than others, especially at night when a guard on patrol would meet up with others and stop for a chat. Often a guard on his own in a watch tower would appear to be dozing off rather than remaining vigilant and keeping an active lookout. There was sometimes, a section of fence which, for a short period of time, was not under surveillance. Then of course there was the well guarded main gate. There was at intervals, a lorry leaving the camp loaded with rubbish or a builder’s lorry or van. In a large camp there was a constant need for a builder, plumber or electrician to do some repair work. Those vehicles were supposed to be, and usually were, thoroughly searched before being allowed to leave but over time some guards became less than thorough in the search, and many a POW had gone through the main gate hidden under a pile of rubbish or concealed in a builder’s van.

I started to give some thought again as to what to do if I did manage to escape. Before the war was a time when package tours and mass tourism did not exist, so I, like the vast majority of POWs, had never been out of England before so we had no idea where most of the towns in Europe were and had a somewhat sketchy idea of the relative position of many of the countries. Getting back to England was out of the question because even if one managed to get across Germany and France, there was no way that we could get across the English Channel. The favoured place to try and get to was Switzerland, although we were not sure what would happen to us if we did manage to get there. Finding Switzerland would not be easy. We knew it was south of Germany, but with no map and compass and the Germans having removed most of the signposts, as we had done in England, it would be all too easy to miss Switzerland and find oneself in Austria or perhaps Czechoslovakia or Hungary. With the invasion of Europe now well underway, I reasoned that by heading in a westerly direction, I would arrive somewhere in France and hopefully meet up with some contingent of the allied forces.

The two red squares show the approximate position of Stalag IV A (the easternmost) and Karlsbad, Spencer’s final destination, a distance of about 300 miles as the crow flies

It was always a surprise to Allied POWs arriving in the Stalag to find how much greater freedom the French were commonly allowed than others. Parties of largely unsupervised French men seemed to be moving in and out of the gate, going to work at rail depots, farms and villages almost with the same ease as local civilians. It suited the Germans to send them out unsupervised. Saving on guards, confident of their return. Their home country was of course occupied by the Germans who could easily take reprisals against their families if they did attempt to escape. With so many somewhat scruffily dressed French men and forced labourers from other occupied countries moving freely around, albeit in a limited area, I reasoned that if I could avoid being stopped and questioned by the police or any military personnel and also avoid raising the suspicion of any civilian who saw me, I stood a reasonable chance of achieving what was known as a ‘Home-Run’.

The Germans in most cases abided by the Geneva Convention with regard to captured POWs provided you had not changed into civilian clothing. You were interrogated and then returned to the POW camp you had escaped from; your punishment usually consisted of a short spell in solitary confinement. Now, however, notices had appeared in the camp from the German High Command stating that in future all recaptured escapees would be shot. Although somewhat disquieting, we assumed that it was an indicator that as the German forces were now so heavily engaged on two fronts, they did not have the resources to man their various checkpoints and carry out spot checks.

I then became more confident that I could get away without being challenged. I might have been less sanguine had I known about the escape that had taken place sometime earlier from Stalag Luft III at Sagan. In this event which was later portrayed in the film “The Great Escape”, 76 men escaped through the tunnel. Of these, only three made a successful home-run, the rest being re-captured and fifty were shot by the Gestapo. Perhaps it is just as well that I did not know about it at the time. However, notwithstanding the many problems, another chap and I decided to have a go.

We started to survey the entire perimeter fence and selected a stretch where the bottom of it appeared to be in need of repair. After dark each evening we started to watch the behaviour of individual guards and after a few days of watching we saw our opportunity. The patrolling guard had just passed and we could just make him out, at the far corner of the fence, in conversation with another guard. Also, the chap in the nearest guard tower was facing away from us and not appearing to be particularly active. We quickly crawled across no-man’s land to the fence, then cutting away a bit more of the bottom of the already damaged fence with some cutters that had been smuggled into the camp, crawled underneath it and then wriggled our way across the open ground into the darkness away from the light of the camp. We then made a dash for the distant hedgerow. We lay there for a few minutes but no hail of bullets came our way and no shouts were coming from the camp. We breathed a sigh of relief as we realised we had managed to escape unscathed and unnoticed.

Moving on, we soon struck a main road and set off along it in what we hoped was the right direction. There was little traffic on the road and although at times we did come across other pedestrians in the vicinity of small villages, we just kept walking and they took no notice of us. Although we were still in British Army uniforms, the khaki jacket and trousers I had on, had been worn for over two years and now looked very scruffy and not instantly recognisable as a British soldier’s uniform. In the early hours of the following day we saw a battered looking barn in a field, it appeared unused so we decided to stay there for a while to get some sleep. The following day we could see many vehicles travelling along the road and occasionally a military convoy so we decided to stay put until nightfall. The evening passed without incident, although we were constantly full of apprehension in case anyone should stop and speak to us. The days followed on in a similar pattern. Occasionally, on the approach to a village we would see military vehicles parked on the roads, we would then withdraw to the woods. By morning they had gone.

After a few days we passed over the border from Germany to Czechoslovakia, or at least the part known as the Sudetenland, which was predominantly German speaking and had, in any case, been annexed into Germany after the Munich conference of 1938. In earlier times I am sure we would have come across Military or Police personnel who would have asked for the inevitable papers that everyone had to carry. Fortunately we were never challenged by anyone although we had a few scary moments. We kept clear of bus and rail stations. We had no money or papers and could not speak German.

The main problem we had was finding food. Water was no problem as all villages tended to have public water pumps, water features or troughs, but finding something edible was a serious problem. I am not sure how many days we had been walking, but looking back on a map many years later, I realised we had only walked about two hundred miles so had made slow progress. We eventually arrived at the town of Karlsbad. I suppose feeling emboldened by our success so far, and feeling very tired from the effects of lack of food, we continued through the town in daylight in the hope of finding food. It was at this time that I started to feel giddy and staggered into a fence to stop myself falling over. To my amazement a German woman passerby no doubt noticing I was in a very weak condition grabbed hold of me and realising I was too weak to be left she, with the help of my companion, took me further along the road to her house. Her name was Frau Radeck. She lived on the main road with her two teenage daughters Gerda and Ushi. She also had a son in the German Army in Norway and her husband, also in the army, was in a POW camp in England. We were very surprised by her actions. The penalty for assisting escapers and evaders was usually death after brutal interrogations. Her whole family would have been taken.

We were both much weaker than we thought. A bed was made on the floor of her front room and after a couple of nights of sleep and being fed we recovered. The next problem was what to do next. When we set out from Bad Shandau, we had no idea as how far we had to go. Since capture we had no maps or compasses. All news was hearsay from guards and the local population. We did listen to Frau Radeck’s radio and learnt that the nearest Allied troops were the Americans who were some distance to the west. We were considering moving on or we had the option of remaining with Frau Radeck in her home until the Americans arrived. We did not want to compromise the family’s position, but on the third day our minds were made up for us. There was quite a commotion in the town with heavy gunfire. The Russians had arrived looking like a scruffy rabble rather than a fighting force; in fact some looked like they had been released from POW camps. There was no armour, just a few lorries. They seemed to be living off the land and they began to forage for food throughout the village. We tried to speak with them but they hadn’t a clue as to who we were. They probably thought we were German deserters and treated us with deep suspicion.

During the night we heard a lot of spasmodic shooting and many people were killed. Word got around that we were in the town and the town Burgomaster appeared, probably under the misapprehension that we were an advance unit of the British Army. We went with him to the hospital where the Russians had taken all the blankets and sheets from patients and had smashed up the dispensary. We were asked to intervene on his behalf but we reckoned our intervention would not carry any weight. After two more days with more shooting it was time to take stock of the situation. The Russians were obviously part of the main ‘shock army’, very trigger happy, not friendly, with the Russian Army following behind. We were now known in the town and it was possible that the German army or SS might mount a counter attack so we decided it was time to leave. We said a hasty thank you and goodbye to Frau Radeck and her daughters and we headed out of Karlsbad in, we hoped, the direction of the American forces.

The rest of our journey was quite uneventful moving mainly at night. We still had to be careful near villages keeping a keen eye out for enemy soldiers and vehicles. Eventually, much to our relief we sighted a contingent of American soldiers. We did not stay long with the Americans. We were given a meal and thoroughly sprayed with disinfectant or delousing powder and given a shower. We were then put on a plane and flown to Brussels. Handed over to the RAF we boarded a Dakota DC3 and flew back to England landing at Haywards Heath. I don’t think I was there for more than a day or two; another shower, issued with a new uniform and underclothes, and further interrogation to establish who I was.

So, having been issued with a ration book, some money, an army pass for two months leave and a railway warrant to Hendon Station, I clambered into the back of an Army three ton truck and headed for the station and home. It was 1945 and I was now 22 years old.

Geoffrey Spencer, Signals Platoon, 2 Royal Hampshire Regiment

For Geoffrey that was not the end of his wartime chapter. He never forgot the Radeck family who came to his aid when he needed help at great risk to themselves. Being German, they faced execution if caught with ‘the enemy’. They were thrown out of their home at the end of the war and a Czech family confiscated all their belongings and property. It is thought that they may have ended up walking into Germany as refugees and possibly ended up in a displaced persons camp where they became lost to the world. Over the years Geoffrey has tried to find them but to no avail. But as an old soldier he does not give in easily.