World War 2 Escape Lines – France & Belgium

The Pat O’Leary Line

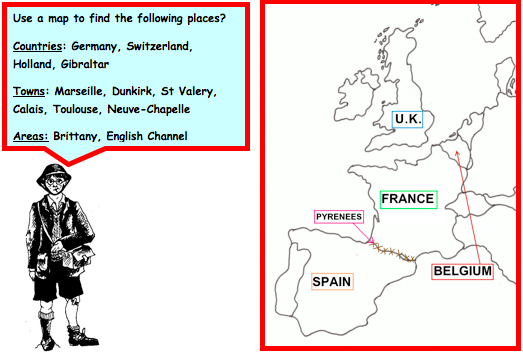

This line began in 1940 when stranded soldiers were ‘helped’ by French and Greek civilians in southern France. Following on from Dunkirk, St Valery and Calais, the ‘helpers’ assisted allied servicemen with their efforts to evade the Germans, and make their dangerous journey from northern France to Marseille; here they would be met by mountain guides and couriers who would take them over the Pyrenees into Spain and onward to Gibraltar.

Although the line originally ran from northern France to Marseille, it later expanded its activities to assist those servicemen who had made their way to neutral Switzerland. As well as making their escape over the mountains, servicemen were also evacuated by sea, taking them from the beaches of southern France, direct to Gibraltar.

Many of the ‘helpers’ were arrested, and the line almost closed when enemy agents infiltrated the group in early 1943. Despite this setback, the line re-routed through Toulouse and ran until the end of the war.

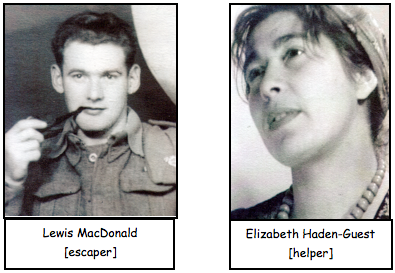

| Lewis MacDonald was a wireless operator in the Royal Signals when he was captured at Neuve-Chapelle after fighting in the rear-guard action at St Valery. On his fourth escape attempt he was finally successful, although suffering from the beatings that he had taken at the hands of the Gestapo. MacDonald risked travelling south from Paris by train, but found himself sharing a railway carriage with a lady and a small boy and two German officers! After a while the boy began speaking to his mother in English – MacDonald remained silent. Fortunately the Germans left the train and MacDonald was able to speak to the woman, who was apparently trying to get to England, and eventually America, to join her husband. |

After many adventures trying unsuccessfully to get across the Pyrenees into Spain, MacDonald again found himself locked up – this time in a French POW camp. The escape committee in the camp arranged for MacDonald to escape. Outside the camp he discovered that his contact was none other than the lady he had met on the train – Elizabeth Haden-Guest, a member of the Pat O’Leary escape line. Elizabeth took him to a safe-house in Marseille where he joined a group of evaders who were about to cross the Pyrenees into Spain. Then it was onwards to Gibraltar and home.

The Shelburn Line

The Shelburn Line was mainly in use between December 1943 and August 1944.

It was different from many of the other mainland escape lines because it often took groups of evaders to safety, rather than just one or two men at a time.

The escape line’s route was primarily by sea. Evaders were taken to the Brittany coast then from there they went by motor gun boats [MGBs] across the English Channel back to England.

| Flying Officer Gordon Carter, a Canadian, was serving as a navigator in 35 Squadron RAF when on the night of 13th February 1943 his Halifax was hit by heavy flak while bombing the German submarine base at Lorient in Brittany. Gordon parachuted out and landed in a ploughed field. A young French boy saw him land and helped him hide his parachute, then led him to a farmhouse, where he stayed overnight. |

Gordon was then moved between several safe-houses. He eventually met up with a man called Guy Dubrevil, a secret agent working from London, who arranged for him to be picked up by a submarine and taken back to England. Unfortunately, although Gordon waited off the coast all night in a small dinghy, the submarine never arrived.

Gordon returned to his safe-house then a new courier, Georges Jouanjean arranged moves to other safe-houses in the area. George’s sister Janine Jouanjean was given the job of taking Gordon between the safe-houses on bicycles.

After many safe-houses, and many adventures, Gordon was eventually taken back to England on a rather dilapidated fishing boat called the “Dalc’H Mad”. In May 1945 he returned to Brittany to find his courier Janine and they married on 11th June 1945.

After many safe-houses, and many adventures, Gordon was eventually taken back to England on a rather dilapidated fishing boat called the “Dalc’H Mad”. In May 1945 he returned to Brittany to find his courier Janine and they married on 11th June 1945.

The Comete Line

The Comete line was a Belgian run organisation for escape and evasion.

When the Germans occupied Belgium in 1940, many Belgians wanted to continue the fight for freedom in any way that they could. Resistance started by simply visiting those British servicemen who had been injured while fighting in northern France and had then been left behind in Belgian hospitals as the British Army withdrew.

After the fighting at St Valery, Dunkirk and Calais, many allied servicemen who had been captured by the Germans were marched through Belgium and Holland to the River Rhine. From there they were taken on barges to Germany, then later to POW camps, many of which were situated in Poland. On the marches through Belgium and Holland the prisoners were lightly guarded, making escaping relatively easy, so some were able to simply slip away and begin their evasion. Local villagers secretly assisted the escapers and evaders and provided them with food and shelter.

In 1941, Comete organised an escape route from Brussels, in Belgium, to the western Pyrenees. The route then crossed the Spanish border and from there the evaders were eventually moved south to Gibraltar.

| Flight Lieutenant Albert Day of the Royal Canadian Air Force, was serving with 77 Squadron of the RAF, when on the night of 5th/6th August 1941 he parachuted out of his damaged Whitley bomber over the Ardennes on the return journey from a bombing raid on Koblenz. The plane had been hit by anti-aircraft fire, but before baling out the crew managed to destroy all codes and sensitive material that would be of possible use to the enemy if the wreckage was found. |

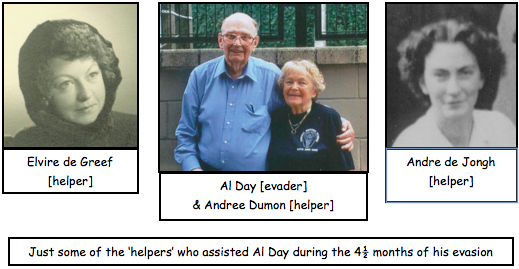

Once on the ground Al spent ten days evading before he was contacted by a Belgian helper called Henri Mares. Mares took Al to a safe-house then, for several weeks, he was moved between many other safe-houses, both for his own safety and for that of the helpers. Eventually he was moved to Brussels travelling by bicycle and train – always remembering to keep a short distance away from his guides in case of capture.

In Brussels Al stayed at the home of Mme Dufour while false papers and identity cards were arranged for him. Madame and her children Jean and Monique cared for Al well, making him feel like one of the family. Unfortunately the safe-house was compromised and Mme Dufour and Jean were arrested.

Monique managed to smuggle Al away, and he was moved to the safe-house of Mme Deporque. It was there that he learned that his false papers had arrived and it was time to ‘go down the line’, although he was not well and recovering from pneumonia. However Al did begin the journey on 22nd December; guided first by Frederic de Jongh and then passed to ‘Nadine’ [the code name for Andree Dumon] who took Al and three other airmen to Valenciennes on the Belgian / French border.

From Valenciennes the group was taken by Andree de Jongh on a very long train journey via Paris to the safe-house of the De Greef Family on the Spanish border. On Christmas night 1941 the party was guided over the Pyrenees and across the River Bidassoa into Spain by the mountain-guide Florentino. From there the airmen were passed into the safe-keeping of the British Consul.

Al Day returned safely to England and resumed combat operations, as a fighter pilot with 418 Squadron RCAF.