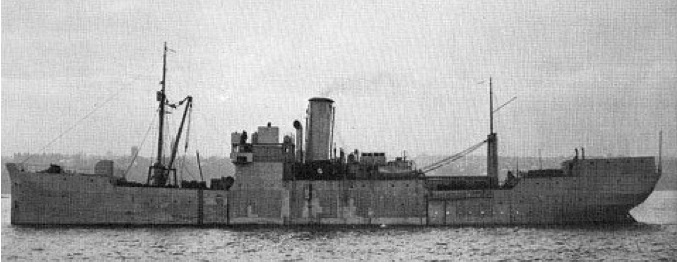

HMS Fidelity

WW2 created many anomalies, mysteries and intrigues amongst the unusual organisations, agencies, individuals, Special Forces and private armies that evolved at that time. Records have been engulfed by the vast WW2 archives and are only likely to be unearthed by intrepid researchers.

The story of ‘HMS Fidelity’ was shrouded in secrecy for most of its operational life and when the ship disappeared off the Azores on the night of 30 December 1942 it also disappeared from the Navy records. There were no survivors; the only record comes from the German Naval archives which reported its sinking by the captain of U435 in the late afternoon of the 30th December 1942. The U-boat and all its crew were lost shortly afterwards, so there can be no corroboration.

Speculation is still rife as to what happened to the ship and also to the men of T Company 40 Commando who were on board. Where were they going, and what was the operation? There were no survivors of the Commandos or of the ship’s crew. The fact that the story was told at all is down to two men, both of who had served on the ship in the early days with SOE and later became involved with other undercover activities.

Albert Guerisse, alias Lt Cdr Pat O’Leary GC DSO RN, known as ‘Soigne’ on board the ship, and later to become the organiser of the Pat O’Leary Escape Line, and Lt George Archibald RN, known as ‘Bernard’ on board ship told their story in 1957, when it was written down for the first time.

In the 1930s, two individuals working for the Deuxieme Bureau in French Indo-China met and became soul mates. Both were on dangerous intelligence duties in Japanese occupied China and in Vietnam. Both were experts in sabotage and explosives and were crack shots with pistols and rifles. In October 1939, the pair, Claude Peri and Madeline Bayard were recalled to France and sent on sabotage operations against German shipping. This they accomplished with great skill using the new explosive known as ‘plastic’. On returning from a successful operation to blow up enemy shipping with limpets and plastic in Las Palmas, Peri was under orders to return to Morocco but, appalled by his country’s capitulation, he left the convoy under radio silence and altered course for Gibraltar.

There was a violent struggle with the crew members, during which Claude was shot and nearly died, but the ship’s crew were overpowered and the ship, which had on board a hoard of plastic explosives and weaponry, sailed to Gibraltar, arriving on 22 June 1940. There Claude offered his services to British Intelligence and the Royal Navy.

Seconded to British Intelligence, Claude and Madeline toured the bars of Gibraltar for additional crew. The Free French Headquarters in London were decidedly unhappy with the situation! The Royal Navy renamed the ship HMS Fidelity and gave the ship’s officers commissions in the Royal Navy. After a refit at Barry, in Wales, and heavily armed, Fidelity became a ‘Q’ ship under the control of the Special Operations Executive to be used for the insertion of agents, arms and ammunition into France, and the extraction of agents and evaders from France.

There was violent disagreement between Claude, now a Commander in the RN, and the RN authorities regarding the position of Madeline. The Royal Navy did not sanction women aboard ship and Claude would not sail without her. Eventually Madeline was commissioned as a cipher officer in the WRNS and became the only woman to serve aboard a RN ship during WW2.

Claude, whose origins are uncertain, possibly Corsican or Italian, but a confirmed French patriot nevertheless, chose the undercover name of Jack Langlais. He was a very strong character, with a ‘short fuse’ and an uncontrollable temper. He was single minded with a disregard for the law and authority, and a fearless buccaneer whose word was law and ruled with his fists. On assuming command of Fidelity Langlais still displayed evidence of a jaw injury delivered by a bullet.

Madeline was given the name of FO Barckley, WRNS. Although attractive and alluring, at times she was often harder than the men who worked alongside her. Described by the crew as enchanting, ruthless, dangerous and uninhibited, she hardly ever left Claude’s side. The remainder of the crew were characters in their own right who adopted English names to protect their identities, and those of their families in France and Belgium. When they had settled on names, Langlais informed his crew that from that point they had only one name – their nom de guerre. It was agreed. So the crew of the Fidelity were married, decorated, fought and disappeared under their assumed names.

HMS Fidelity’s first operation was to collect Polish escapers from the French coast at Cerbere. On the 26 April 1941. A small fishing boat, under the command of Pat O’Leary, left the mother ship to collect the men and entered the harbour. It arrived safely, but while waiting for the evaders O’Leary was compromised; the French Gendarmes were not satisfied that he was just a fisherman putting out to fish. He left quickly but was pursued by a fast police boat, arrested and placed in Saint-Hippolyte-du-Fort. Pat’s days with Fidelity were over. O’Leary escaped and later became the leading player in the escape line network based in Marseille which was eventually to bear his name. Fidelity took part in other operations along the French Mediterranean coast and the Gulf of Lyons involving the insertion of agents and the collection of evaders.

On the evening of the 30 December 1942, Fidelity experienced engine trouble on its way to Freetown. It was in the Azores, and had broken off from convoy ONS154 due to the engine problems. The lone ship was attacked by a wolf pack of U boats. U225 fired the first torpedo, which missed. An hour later U615 fired three further torpedoes, two of which hit the Fidelity. By mid-afternoon, radio contact had been lost when U435 fired two further torpedoes. None of the crew or the Commandos on board survived.

Although the RN later acknowledged that HMS Fidelity did valuable work along the French coast it castigated her captain and crew. The captain was deemed uncontrollable and unsuitable for convoy duties, and the crew poorly trained. Pickups had been left un-logged and paperwork was lacking. The decision to have placed T Company of 40 Commando on board was considered highly questionable.