The Story of Sgt Bud Owens

Bud Owens, a brave young man from Pittsburgh, died in 1943 in the snowy Pyrenees Mountains at the end of a desperate trek to escape occupied France into Spain after being shot down over Normandy. The B-17 gunner’s remains are buried in the Ardennes American Cemetery in Belgium under a white cross, one among thousands marking the graves of Americans who helped liberate Europe from Hitler’s war machine. His is another of the millions of sad war stories from that time, but he has not been forgotten — in France or in America.

Earlier this year, Staff Sgt Owens’ great-niece, Hayley Hulbert, 19, of Bethel Park, and her aunt, Colleen Brennan, 63, of Plum, joined a French team of guides and an American documentary maker to retrace his journey with the French resistance from Normandy to a forbidding mountain pass in the Pyrenees where he died of exposure and exhaustion with two other airmen. Ms. Hulbert, a student at the University of Pittsburgh studying to become a teacher, had never been on a plane before, let alone a mission to recreate history or an 11-hour hike into the mountains.

Earlier this year, Staff Sgt Owens’ great-niece, Hayley Hulbert, 19, of Bethel Park, and her aunt, Colleen Brennan, 63, of Plum, joined a French team of guides and an American documentary maker to retrace his journey with the French resistance from Normandy to a forbidding mountain pass in the Pyrenees where he died of exposure and exhaustion with two other airmen. Ms. Hulbert, a student at the University of Pittsburgh studying to become a teacher, had never been on a plane before, let alone a mission to recreate history or an 11-hour hike into the mountains.

“It was kind of the best vacation I’ve ever had,” she said.

But it was more than a vacation. She wanted to honour Francis “Bud” Owens of Lawrenceville — who, at 21, was just a couple of years older than she is — and try to understand what he and other downed airmen endured in the dark years of World War II. “Before, I didn’t really know the whole story,” she said. “Now there’s a new appreciation for all they went through.” Ms. Brennan, whose father, Jim Owens, is Bud’s brother, had grown up with the story, but she now had the chance to see where it happened.

“To me, it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” she said.

The excursion, headed by Normandy battlefield guide Geert Van den Bogaert and filmed by Wisconsin filmmaker Jed Henry of Recon Productions, was called “In the Footsteps of Bud Owens” and set up as a nonprofit enterprise with the idea of preparing a documentary to sell to a museum, to websites, to gift shops or possibly to a television outlet. The organizers said they hoped to give young people like Ms. Hulbert an appreciation of the “tremendous fortitude and courage” of the World War II generation and a connection to the past.

In addition to Ms. Hulbert, the team included a young Frenchman, Louis Hatet, whose great-grandfather, Andre Rougeyron, was a resistance leader in Normandy, and two airmen from the 381st Training Group at Vandenburg Air Force Base in California, where a training facility was named for Sgt. Owens in 2012.

With money raised through Gofundme, the team traveled by trains, planes and automobiles — and a lot on foot — across France, visiting the old stone barn where the resistance hid Sgt. Owens for months, then a series of former safe houses in Paris and finally the mountains before ending the journey at the Belgian cemetery. The most arduous part was the last day of the three-day mountain hike. Ms. Brennan rode in a support vehicle, but the rest made their way up to Arinsal in La Massana, some 9,000 feet in the peaks of remote Andorra. Ms. Hulbert, a star soccer player, said the climb was tough despite her soccer conditioning and her training hikes in South Park carrying a 25-pound pack.

“Today we mounted Port d’Arinsal [part of La Massana],” the team wrote on the project’s Facebook page. “It was a very challenging hike (11 hours!) and one can easily understand why Bud Owens and two of his fellow evaders did not make it in 1943, seeing the conditions they faced. Plenty of time for our group to contemplate and meditate before receiving a wonderful welcome by the people of La Massana.”

Bud Owens was one of 10 children who grew up on Calvin Street in Lawrenceville, and he graduated from Schenley High School and enlisted in the Army after Pearl Harbour. By May 1943, he was in England as a B-17 gunner with the 381st Bomb Group. He quickly distinguished himself with an act of courage in June. As his unit was preparing for a bombing run to France, a bomb being loaded on a plane blew up, leading to a cascade of explosions. Sgt. Owens, who had been cleaning the machine guns on his own plane, risked his life to pull an injured man to safety. Twenty-three others died.

He flew several missions as a waist gunner, and on July 4, 1943, his unit attacked an aircraft engine factory in Le Mans, France. As the formation approached the target, an anti-aircraft shell burst below his plane’s radio room, killing three of the 10 crew members and cutting the oxygen lines to the back of the aircraft. The pilot descended to 21,000 feet and headed back to England, but German fighters shot up the plane and Lt. Olaf Ballinger gave the order to bail. Sgt Owens, realizing that no one had heard from the radio operator, John Lane, made his way to the radio room, found Sgt Lane unconscious, revived him with oxygen, helped him into a parachute and held the door while he jumped. Then Sgt Owens bailed out too.

The plane crashed near the village of La Coulonche in Normandy. Sgt Owens and four others parachuted into the French countryside, where they were taken in by the French resistance and sheltered in barns and farmhouses. Sgt Owens landed in a field, where a farmer took him to a local teacher, who in turn took him to another home where he met up with Lt. Ballinger. From there, they walked 4 miles to Saint-Opportune, where they were taken in by Andre Geslin and housed in a stone barn. They remained there for three months, hiding from German patrols and only coming out at night.

Ms. Hulbert, Ms. Brennan and the other members of the team who visited France met Mr. Geslin’s daughter, Jeanine Gandeboeuf, who was 3 at the time of the crash. Her family still owns the property, although the barn is empty now.

“They had a reception for us and everything,” Ms. Brennan said. “She cried when we left.”

After three months in the barn, the resistance members, orchestrated by Mr. Rougeyron, moved Sgt Owens and Lt. Ballinger to a post office in Champsecret, and from there to a series of safe houses in Paris, where they met with other downed airmen and French officers trying to get to neutral Spain. Food was in short supply, and clothing a constant problem. Sgt Owens was 6 feet 3 inches, huge by French standards, and Lt. Ballinger was big, too. Old photos show Sgt Owens in an ill-fitting French jacket. From Paris, the resistance put the men on the night train to Toulouse and then to St Girons, and from there they walked to the town of Suc, where they would begin their ascent into the Pyrenees. The climb would be a challenge for healthy hikers, as Ms. Hulbert discovered, but nearly impossible for malnourished airmen who had been hiding from the Germans for months.

Lt. Ballinger dropped out because of leg cramps, but the others forged on. One airman, Harold Bailey, became sick and collapsed after taking too many Benzedrine tablets in an attempt to generate enough energy to make the climb. Sgt Owens and another airman, William Plasket, had to drag him through the snow. Their attempt to save him probably sealed their fate.

“Owens and Plasket had been dragging Bailey for approximately eight hours, and were themselves almost completely exhausted,” a 1950 Army report says. “At this point the party was at an altitude of approximately 1,800 meters. The snow was about three feet in depth. The garments of the men were thin, and they had no underwear or overcoats. Due to an insufficient food supply over a period of weeks, their physical condition was very poor.”

The party had been hiking for 30 hours, but as they neared Arinsal in Andorra, Sgt Owens, Sgt Plasket and Lt. Bailey could not go on. The four other members of the party couldn’t help them. The French guides tried to get the three to move because it was getting dark and there was no shelter, to no avail. One of the French guides, Emile Delpy, drew his gun and said he’d shoot them if they didn’t get up. They didn’t respond and he fired a shot into the snow, but they still didn’t move. The party left them behind and moved on.

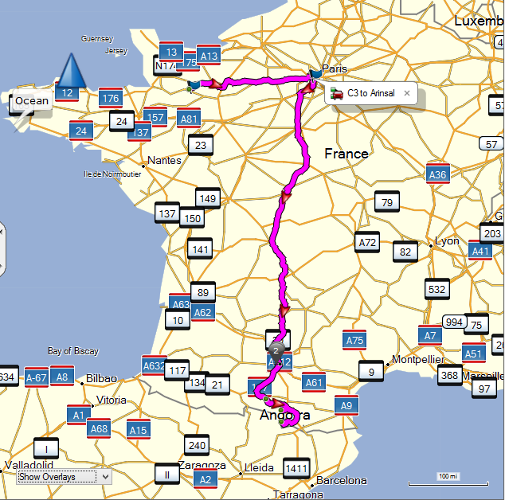

This is the approximate route followed by Bud Owen and his colleagues. Distance is some 750 miles. From St Girons to Suc is about 30 miles, and from Suc to Arinsal about 20

No one knows for sure, but the three men likely died of exposure in late October.

The bodies, devoid of any identification, were discovered the following spring by an Andorran mountain patrol and buried in a local cemetery. An Army mortuary unit tracked the missing airmen to the cemetery in 1950. At the request of his family, Sgt. Owens’ remains were removed and interred at the Ardennes cemetery on Oct. 1, 1951.

That morning in Pittsburgh, his family attended a requiem high Mass at St. Mary Church.

That morning in Pittsburgh, his family attended a requiem high Mass at St. Mary Church.

This July 11, near the end of their European adventure, Ms. Brennan and Ms. Hulbert held their own ceremony at the Ardennes grave. Among the field of crosses, they stood arm in arm and silently paid tribute to a young warrior who died before his life really began.

Anyone interested in a more detailed explanation of the fate that befell Bud Owens and others can find it HERE This account was compiled from official reports.

This article is reproduced with the permission of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette