There are a variety of methods for inserting soldiers into battle in modern warfare, and some of these were developed during WW2. The Parachute Regiment was formed in 1940 on Churchill’s orders, and the Special Air Service Regiment in 1941 by David Stirling. Both these Regiments could be delivered by air, and in their short history both have distinguished themselves in nearly every operation and war since WW2. Their standards are high, and training and selection difficult. There was however a third Regiment that fought and died alongside these men. Hardly mentioned today, The Glider Pilot Regiment earned its wings, and fought shoulder to shoulder with airborne soldiers. Although todays Army Air Corps carries on the traditions of the Regiment, albeit in helicopters, the original Regiment had some of the toughest training of any unit in WW2. They also suffered the highest death rate in training of any unit in WW2 – and since. They were fighting soldiers and also trained aircrew. No one was accepted into the Regiment below the rank of Sgt. They carried out aircrew training, and the majority were young officers and warrant officers. They were a unique group of men who were awarded DFC’s alongside MC’s. Only the Germans and Americans also used glider troops. Neither trained their Glider Pilots to the same high standards. The American pilots landed their gliders and then returned to their own lines, their job complete. The British pilot, when not injured in the landing, picked up his rifle and equipment, put on his red beret, and joined up with the airborne troops he had delivered into battle, and continued the fight as an airborne soldier.

Formed in 1942, the Regiment was bloodied on Operation Freshman in 1942.The first glider borne operation on the Heavy Water plant in Telemark, Norway, turned into a disaster because of poor weather conditions. One Tug aircraft and its glider flew into a mountain, and the entire complement were killed; the second glider’s tug rope froze and snapped. The glider crashed, resulting im many casualties. All were captured, and after harsh treatment by the Gestapo were all executed.

The first major glider operation, Op Husky, was the invasion of Sicily in 1943. The Regiment lost 57 pilots, and many more airborne troops, due largely to inexperienced American tug pilots, who, as soon as flak started, released their gliders over the sea, forcing over half of the gliders to ditch in the sea. As all soldiers know, you do not swim well with about sixty pounds of kit and ammunition attached to your body. Another war nearly started with Airborne troops searching out American tug pilots. Back at the base location, the American crews hid, and British glider troops were placed under close arrest for forty eight hours until tempers had died down. Later a strong bond was forged between Glider Pilots, the troops, and the Tug Pilots both RAF and USAAF.

The two main gliders in use were the HORSA and HAMILCAR Gliders. The Horsa was designed to carry twenty five men in battle kit or a jeep and trailer, or a 6 pdr field Gun.It was constructed from 3 ply wood, with a large perspex windscreen. Many pilots were badly injured on landing when they were thrown through the perspex window, or being injured when the load, a jeep or field gun shunted forward.

The Hamilcar was a very large glider. Built by the Wagon Rail Carriage Company in Birmingham. It could carry up to forty troops, but mainly carried light armoured vehicles, jeeps, and field guns. Again the pilots suffered on landing, although in a higher position than the Horsa, they were often injured and crushed by the load when the glider hit an obstacle. Both gliders had no protection from small arms fire or flak. Everything relied on the skill of the pilot to manoeuvre and steer his glider. In some cases gliders were steered to land between trees to snap off the wingspan and slow the aircraft down.

The Hamilcar was a very large glider. Built by the Wagon Rail Carriage Company in Birmingham. It could carry up to forty troops, but mainly carried light armoured vehicles, jeeps, and field guns. Again the pilots suffered on landing, although in a higher position than the Horsa, they were often injured and crushed by the load when the glider hit an obstacle. Both gliders had no protection from small arms fire or flak. Everything relied on the skill of the pilot to manoeuvre and steer his glider. In some cases gliders were steered to land between trees to snap off the wingspan and slow the aircraft down.

The Glider Pilot Regiment distinguished itself in every operation it took part in, and often took more casualties, as a percentage of its Regimental strength than any other unit in WW2. In 1944, The Regiment took part in the D Day landings in Normandy, Op Market Garden at Arnhem and Nijmegen, and in 1945 the Rhine Crossing, all in quick succession. On the night of the D-Day 05/06 June 1944, the first troops to land in Normandy were men in Gliders.

Major Howard of the Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, with six Platoons, had the task of taking the bridges over the River Orne and Caen Canal before they could be blown by the enemy. His two Staff Sergeant pilots John Ainsworth and Jim Wallwork, had been asked by Major Howard to put the glider down as near to the bridge as possible so that the bridge could be taken before it could be blown. Both pilots knew the problems, would carry out their task, but both expected to be killed, or at least badly injured on landing. They had decided to ram the glider into the bridge defence perimeter.

Major Howard of the Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, with six Platoons, had the task of taking the bridges over the River Orne and Caen Canal before they could be blown by the enemy. His two Staff Sergeant pilots John Ainsworth and Jim Wallwork, had been asked by Major Howard to put the glider down as near to the bridge as possible so that the bridge could be taken before it could be blown. Both pilots knew the problems, would carry out their task, but both expected to be killed, or at least badly injured on landing. They had decided to ram the glider into the bridge defence perimeter.

The pilots did a fantastic job with the glider landing entangled in the defensive perimeter about sixty yards from the bridge. The glider was wrecked, the soldiers were very dazed, some were unconscious and injured, but most staggered from the glider and took their objectives. Both pilots were badly injured having been thrown through the perspex cockpit. Both were later hospitalised. One example of the dedication the Glider Pilots had to carrying out their tasks. Their exploits at Normandy, Arnhem, and the Rhine crossings are legendary.

The pilots did a fantastic job with the glider landing entangled in the defensive perimeter about sixty yards from the bridge. The glider was wrecked, the soldiers were very dazed, some were unconscious and injured, but most staggered from the glider and took their objectives. Both pilots were badly injured having been thrown through the perspex cockpit. Both were later hospitalised. One example of the dedication the Glider Pilots had to carrying out their tasks. Their exploits at Normandy, Arnhem, and the Rhine crossings are legendary.

On the 17 September 44, The Regiment was again in the forefront of Operation Market Garden. One hundred and twenty men of the 21 Ind Para Coy were the pathfinders, and landed successfully from twelve RAF Stirlings.

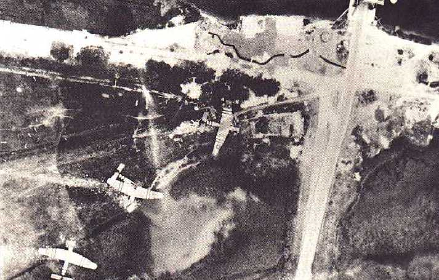

The LZ markers were out, and most of the gliders came in on the northern side of Wolfhezen on Ginkel heath, led in by the markers. On the other side of the railway the men of 1 Para Bde were also landing, together with gliders from 1 Air Landing Brigade. Nearly all of the gliders had a successful landing, and the heath was littered with abandoned parachutes and gliders. Later other troops from the South Staffs Regiment, the Kings Own Scottish Borderers, and The Border Regiment, also landed successfully by gliders on an area known as Reijers Camp. Once on the ground the pilots fought as infantry. All airborne forces are limited in the quantity of arms, ammunition, and rations that they can carry into battle. Airborne assaults depend to a large extent on the element of surprise to help them achieve their mission. They are trained to take their objectives quickly, and then handover to ground forces as quickly as possible. This clearly did not happen at Arnhem. Resistance in the area had been underestimated, and the troops did not know of two SS Panzer Divisions regrouping outside of Arnhem. The ground forces fell behind schedule and met heavy opposition on the way to Arnhem. The Polish Parachute Brigade could not land on schedule because of bad weather in England, and over the drop zone, and if that wasn’t enough to test the military sense of humour, there were problems with radios, aircraft (there was not enough aircraft to drop the men in one go – thus surprise was lost), and the men that were dropped, landed ten miles from their objective of the Arnhem Bridge, and had a speed march to the bridge. Lastly, many of the senior officers lost contact with their troops in the initial stages. The airborne troops were fighting Tiger tanks with small arms. The British 1st Airborne Division, together with the Polish Parachute Brigade, had been given the objective of the bridge at Arnhem. The airborne assault involved some 10,000 men, and the Division suffered nearly 8000 casualties, killed and wounded or captured. They had fought for ten days. Some 2300 were able to withdraw across the Rhine. Despite the losses suffered during Op Market Garden the Glider Pilot Regiment prepared for other tasks. They had suffered many casualties, but continued to be in the forefront of events.

The LZ markers were out, and most of the gliders came in on the northern side of Wolfhezen on Ginkel heath, led in by the markers. On the other side of the railway the men of 1 Para Bde were also landing, together with gliders from 1 Air Landing Brigade. Nearly all of the gliders had a successful landing, and the heath was littered with abandoned parachutes and gliders. Later other troops from the South Staffs Regiment, the Kings Own Scottish Borderers, and The Border Regiment, also landed successfully by gliders on an area known as Reijers Camp. Once on the ground the pilots fought as infantry. All airborne forces are limited in the quantity of arms, ammunition, and rations that they can carry into battle. Airborne assaults depend to a large extent on the element of surprise to help them achieve their mission. They are trained to take their objectives quickly, and then handover to ground forces as quickly as possible. This clearly did not happen at Arnhem. Resistance in the area had been underestimated, and the troops did not know of two SS Panzer Divisions regrouping outside of Arnhem. The ground forces fell behind schedule and met heavy opposition on the way to Arnhem. The Polish Parachute Brigade could not land on schedule because of bad weather in England, and over the drop zone, and if that wasn’t enough to test the military sense of humour, there were problems with radios, aircraft (there was not enough aircraft to drop the men in one go – thus surprise was lost), and the men that were dropped, landed ten miles from their objective of the Arnhem Bridge, and had a speed march to the bridge. Lastly, many of the senior officers lost contact with their troops in the initial stages. The airborne troops were fighting Tiger tanks with small arms. The British 1st Airborne Division, together with the Polish Parachute Brigade, had been given the objective of the bridge at Arnhem. The airborne assault involved some 10,000 men, and the Division suffered nearly 8000 casualties, killed and wounded or captured. They had fought for ten days. Some 2300 were able to withdraw across the Rhine. Despite the losses suffered during Op Market Garden the Glider Pilot Regiment prepared for other tasks. They had suffered many casualties, but continued to be in the forefront of events.

March 24th 1945, was a bright, cold, and clear day. On the airfields of southern England troop carriers, tugs and gliders carrying men of the Air Landing Brigade left the runways. Behind them were the men of the Parachute Battalions. By noon, two Airborne Divisions, the British 6th, and the American 17th, had landed on German soil. Many lessons had been learnt at Arnhem. On this occasion, tremendous artillery support had been given to the airborne army from 21st Army Group. Once again, the Glider Pilot Regiment was leading the way. Following heavy losses at Arnhem, the Regiment been reinforced by many RAF Pilots who had volunteered for glider duties. In a very short time these pilots of the RAF had learnt not only to fly gliders but also to fight as airborne infantry.

March 24th 1945, was a bright, cold, and clear day. On the airfields of southern England troop carriers, tugs and gliders carrying men of the Air Landing Brigade left the runways. Behind them were the men of the Parachute Battalions. By noon, two Airborne Divisions, the British 6th, and the American 17th, had landed on German soil. Many lessons had been learnt at Arnhem. On this occasion, tremendous artillery support had been given to the airborne army from 21st Army Group. Once again, the Glider Pilot Regiment was leading the way. Following heavy losses at Arnhem, the Regiment been reinforced by many RAF Pilots who had volunteered for glider duties. In a very short time these pilots of the RAF had learnt not only to fly gliders but also to fight as airborne infantry.

The LZs chosen for the gliders were the area between Kopenhof and Hamminkeln. The Parachute Battalions dropped north, south, and west of them. Many of the pilots brought their gliders down with 50m of their target, the majority landed within 200m. One glider with the objective of the railway station, actually landed on the railway lines in the station building. The Gliders carrying men of the Royal Ulster Rifles, and the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry were brought down by their pilots on top of their objectives, on both sides of the bridge over the River Issel. The bridge was soon captured. Of the gliders that carried the Air Landing Brigade, ninety percent reached the landing zone. Of the 416 that landed, only 88 were undamaged. The casualties amongst the Glider Pilots was once again very high, nearly 30% killed and wounded. This battle for a foothold in Germany was perhaps the Regiments greatest triumph. The high ground across the Rhine had been captured together with the bridges across the River Issel. An airborne corridor had been created for Montgomery’s 21st Army Group to race into Germany. It was a shared triumph with men of the 17th US Airborne Div who had fought alongside them. Although the Glider Pilot Regiment may now have been consigned to history, the maroon shoulder badge worn by Glider Pilots, the badge of Pegasus, the winged horse and its rider, brandishing a lance, lives on in British Airborne today.

The losses suffered by the Regiment were very heavy, in proportion to its size, which was much smaller than a normal size Regiment. The following figures show the losses incurred during the operations in which the Regiment participated.

Norway November 1942 – 2. Sicily July 1943 – 57. Normandy June 1944 – 34. S France August 1944 – 1. Arnhem September 1944 – 230. The Rhine Crossing March 1945 – 100. Other WW2 Operations 1942 -1945 – 126. A total figure of 550.

Our thanks to ELMS member, and ex-Glider Pilot Geoff Thompson, who proof read the information for me, and also fprovided information on the Regiment. Congratulations are also in order to Geoff, who was just been informed that he is to receive the distinction of Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur from the French Government, for his distinguished service in WW2. The award has been approved by Her Majesty The Queen.

R Stanton 2005