ICI LONDRES was the BBC life line to our friends in occupied Europe. Helpers, Resistants and SOE agents would huddle around their covert radio sets in the evenings, expectantly awaiting their special news, often with lookouts watching for enemy detector vehicles or troops in the area. These people led very dangerous and lonely lives, often with a ‘life expectancy’ of about 90 days in the field – if they were lucky! The BBC ‘Ici Londres’ service was their link with the free world. It was a morale booster. The covert helpers knew that they had not been forgotten and the coded messages given out by the BBC, sounding gibberish to the general listener, meant something of great significance to those ’waiting in the shadows’ for their cue to act, or for confirmation of the outcomes of previous activities – parachute drops of weapons, stores and agents; targets; security warnings; a Lysander pick-up; and the much-awaited successful ‘home runs’ announced by pre-arranged messages and toasted with relief by the helpers.

It all began when an SOE agent in France returned to England for a rest and briefings. He was concerned about the security of his wireless operator, and the high possibility of being compromised whilst broadcasting/receiving on a suitcase radio. He discussed this with SOE and later with the BBC. He wanted less radio traffic, so enabling operators to remain on air for the shortest possible time in order to avoid enemy direction-finding, radio-location and jamming by the Abwehr. The ‘pianists’, as the radio operators were known, had possibly the most dangerous, and arguably the most important, job in the Reseau and had to be protected – they had the skills and held intelligence, codes and passwords. If captured they could expect no mercy from the Gestapo. Therefore the SOE agent suggested broadcasting coded messages to the underground groups via the BBC – everyone would hear the messages, but they would only be of significance to those expecting them.

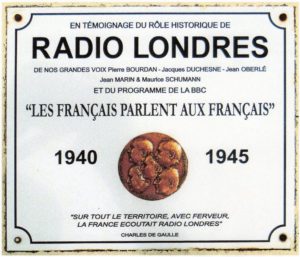

The BBC agreed to use their European Service to broadcast these messages. It was also a way of countering the messages sent via Radio Paris and Radio Vichy. The messages were to follow the normal News broadcasts; the disasters and victories of the day delivered in a calm expressionless voice. Then a slight change to the tone of voice, more nonchalant; followed every night at 1930hrs and again at 2115hrs, by the opening bars of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony imitating the Morse code for ‘V’ – dot, dot, dot, dash – the V, indicating Victory. ‘Ici Londres. Voici quelques messages personnels’, and in a bland voice the ‘gibberish’ messages, given once, then repeated slowly, began to emanate from the cellars of Bush House in London.

Of course the Abwehr and the Gestapo tuned in too, but they thought that the incomprehensible nonsense was designed to waste their time and they generally ignored the messages, and concentrated on jamming the BBC broadcasts. Therefore the BBC regularly adjusted their transmitting frequencies; the listeners retuned their receivers; and business continued! The broadcasts proved to be a success and, as hoped, reduced the capture of ‘pianists’. They now became an official radio station – ICI LONDRES.

The ordinary people of occupied Europe who were able to tune in to the BBC News to follow the progress of the war, mainly French, Belgian and Dutch, were unaware of the significance of the coded messages, so would turn the radio off after the News and hastily hide it in a cold place so that the valves would cool down quickly. They could not afford the risk of listening to gibberish that they could not understand and be caught listening to a banned radio receiver. As radios had been banned in German controlled areas house searches were frequently made at night to detect warm radios and check the frequency settings. To be caught listening to, or with a warm radio, meant a concentration camp. But the ‘underground’ still listened intently!

If expected messages were not read out it meant operations were not on for that night, which meant the continued risk of having to listen every night until they did appear. Most messages were for Resistance and SOE groups, but not were all about the war – sometimes an agent was given personal news, such as the birth of a child.

When evader F/O Gordon Carter reached England, he arranged for a pre-arranged BBC message, – “Sainte Anne a bien fait les choses” [Saint Ann took care of things nicely] – to be sent to his helper group in Brittany, which included the lady who was later to become his wife. Many other evaders arranged similar messages.

In the Spring of ‘44, the radio traffic was profuse. The following are representative of some of the messages sent: “Jean has a long moustache”; “The Postman has fallen asleep”; “Grandma is eating our sweets”; “The cow has had kittens”.

Amongst the baffling messages sent at the beginning of June were the two most important of the war – the first, by the poet Paul Varlaine, – “Les sanglots longs des violons de l’automne” [The long sobbing of the violins of autumn]. The message reached all Resistance groups in France and put all groups on standby for the invasion of Europe. The radios were hidden away, weapons oiled and cleaned and magazines loaded. At 2100hrs on the 5th June, a second message was broadcast calling them to action; “Blessent mon Coeur d’une langueur monotone” [Wound my heart with a monotonous languor]. That night Resistance groups carried out over 1000 pre-arranged attacks on the occupying forces to prepare for D-Day.

The messages were a life-line to France, an invaluable means of communication, morale boosting …………….. AND a concentration camp or death sentence to the listener if caught by the Gestapo listening to “ICI LONDRES”.

In London, every evening while the Blitz was raining down and the Nazis were claiming Paris as their own, broadcaster Franck Bauer took his position behind the microphone at the BBC: ‘Ici Londres. Les Français parlent aux Français,’ he would say. ‘This is London. The French talk to the French.’

His words, broadcast from a little studio in the heart of allied territory, were sent across the Channel and heard by the supporters of the resistance in every corner of wartime France, becoming ingrained in the memories of listeners as a message of solidarity and hope.

Bauer, who was 21 when he was recruited by de Gaulle’s spokesman to join the rag-tag team of Free French members turned DJs, had fled France in 1940, leaving his home town of Troyes on a bicycle and arriving in Liverpool on a ship several days later.

He had never heard of the lofty military exile who had declared himself leader of the Free French Forces in London, but before long he was working as a presenter on the radio station that broadcast de Gaulle’s speeches – most notably the appeal of June 18th 1940 urging his fellow countrymen to join the resistance.

Bauer had no regrets about fighting the war from behind a microphone instead of on the front line. He maintained that Radio Londres did its bit in the war of communication with the Nazi Radio Paris and Petain’s Radio Vichy. He is reputed to have commented, ‘We had a slogan: “Radio Paris ment, Radio Paris est allemande.” [Translated as, ‘Radio Paris is lying, Radio Paris is German’]. Of course they fought us and insulted us. We didn’t give a monkeys though. They were of no importance and we were in the right.’

Frank Bauer died in April 2018, age 99 years.

[Information about Bauer adapted from The Guardian 2009]