Daily Life At Miranda Del Ebro Concerntration Camp

By Maurice Chauvet

(This is a reproduction of an article first published in Newsletter 3 in 2004)

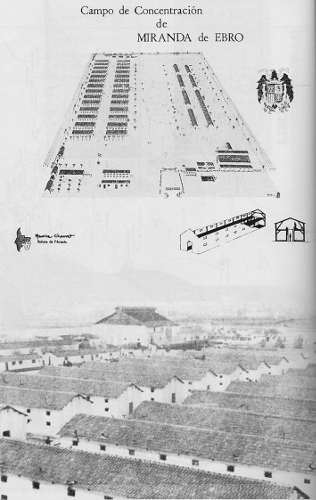

The arrival in Spain of an evader or escaper did not mean that the danger of capture was over. Escapers and evaders still ran the risk of being collected in by the Spanish police and taken to the concentration camp at Maranda de Ebro, near Vitoria. Those unfortunate to end up there usually spent many months of boredom and deprivation, waiting and hoping for their name to appear on the list of men to be released as a result of British diplomatic pressure. Although most people have never heard of Maranda de Ebro, to the men incarcerated there, the name evokes very unpleasant memories.

There were almost 200 concentration camps constructed throughout Spain by the Franco regime. Most housed Spanish nationals who had either supported the former Republican government in the Civil War, or were thought to pose some sort of threat to Franco. Miranda was the largest and originally built to incarcerate the remnants of the International Brigade, some 600 – 700 men of many nationalities. Later it was enlarged to accommodate the men caught trying to escape from France via Spain to Gibraltar or Portugal and, by the end of 1942, the number of detainees had risen to over 5000. It was the only camp used to detain non Spanish nationals who were trying to escape from Occupied Europe. There is little doubt that the Nazi regime were involved in advising the Spanish on how to build and run Miranda, as their Police Attache in Madrid, one SS Stubaf Paul Winzer was sent to Spain specifically to assist the Franco regime.

Understandably, after having managed to escape from the Germans, and the hardships endured in trekking over the Pyrenees, especially in winter, being captured on arrival in Spain was a terrible setback for escapers and evaders.

It was also very disheartening for the brave people in Holland, Belgium, and France, who had risked so much to get them into Spain. But, in spite of the unpleasant detention, most were eventually released and reached England safely. While those not caught by the Spaniards, made it in shorter time, thanks to the untiring work of the British Consuls at Bilboa and Barcelona who used their diplomatic cars to collect them from the border areas (often in a car boot), and take them to Madrid, where the escaper or evader was transferred to another car which took them on to Gibraltar

Living standards at the overcrowded camp were appalling. There was only one tap to serve the whole camp, and the food was awful and insufficient. Boredom sapped the men’s morale and to combat this, Maurice Chauvet, who had been a scout leader before the war, organised and trained men in his barracks as a scout pack so as to keep them occupied. (The padlocked wolfs head with which he signs his Miranda cartoons was the insignia of his Scout pack).

The way the Spanish guards treated the detainees very much depended on the progress of the war. If the Allies were not doing well the treatment was harsh, and the food quality and quantity was poor. But it all improved markedly when a battle had been won and the war seemed to be turning in their favour

The way the Spanish guards treated the detainees very much depended on the progress of the war. If the Allies were not doing well the treatment was harsh, and the food quality and quantity was poor. But it all improved markedly when a battle had been won and the war seemed to be turning in their favour

Eager to join General de Gaulle’s Free French Forces in England Chauvet and two Norwegian sailors had set off from a Moroccan port in a small dinghy, on the 13 October 1941, and started rowing towards Gibraltar. After several days at sea they were picked up frozen and starving, by a Spanish patrol boat and taken to Algeciras, where they were put into a military prison. The Norwegians were liberated by their Consul, but Chauvet was sent to Miranda. Released in April 1943, after 15 months of deprivation, he finally reached England (via Lisbon, Gibraltar, and Casablanca ! ), where he joined 4 Free French Commando, attached to Lord Lovat’s Commando Brigade, and on D-Day, was one of the first Frenchmen to land in France at Ouistreham.

After the war Maurice lived in London, returning to France after the death of his wife, and retired to Ouistreham where he had landed on D-Day with the Free French Commandos. He was the author of an illustrated book for French school children about the Commandos, and had written a book about his long journey to reach England, and his subsequent adventures with the Commandos (Mille et un jours pour le jour J, published by Michel Lafon 1994). He was also technical adviser for the film ‘The Longest Day’.

Maurice Chauvet died at Ouistreham in 2002.

Thanks to member Pierre Wilson for forwarding to the Society the information written by Maurice Chauvet.

If you are interested in further reading the following articles may be of interest.

Campo de Concentration de Miranda de Ebro August 1941 – March 1943 by Władysław Popiołek,