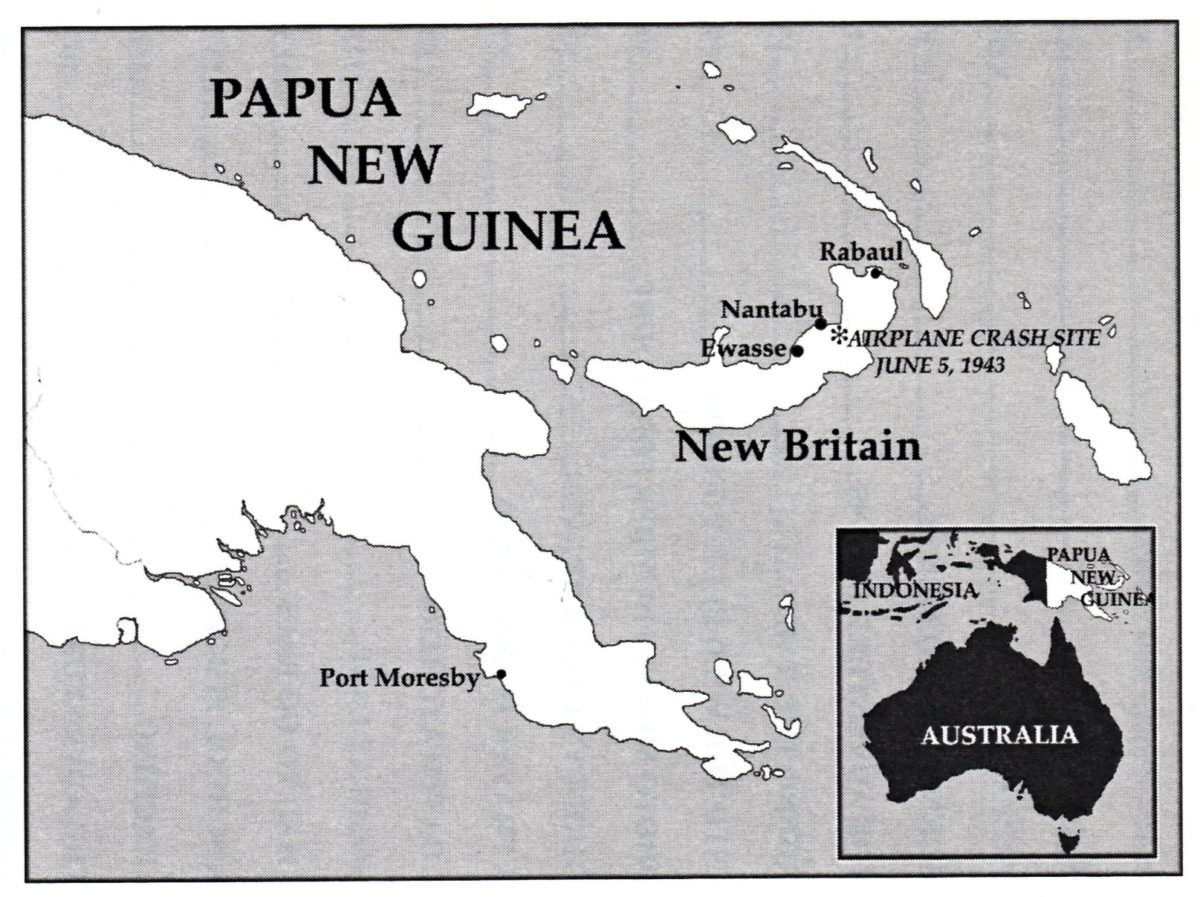

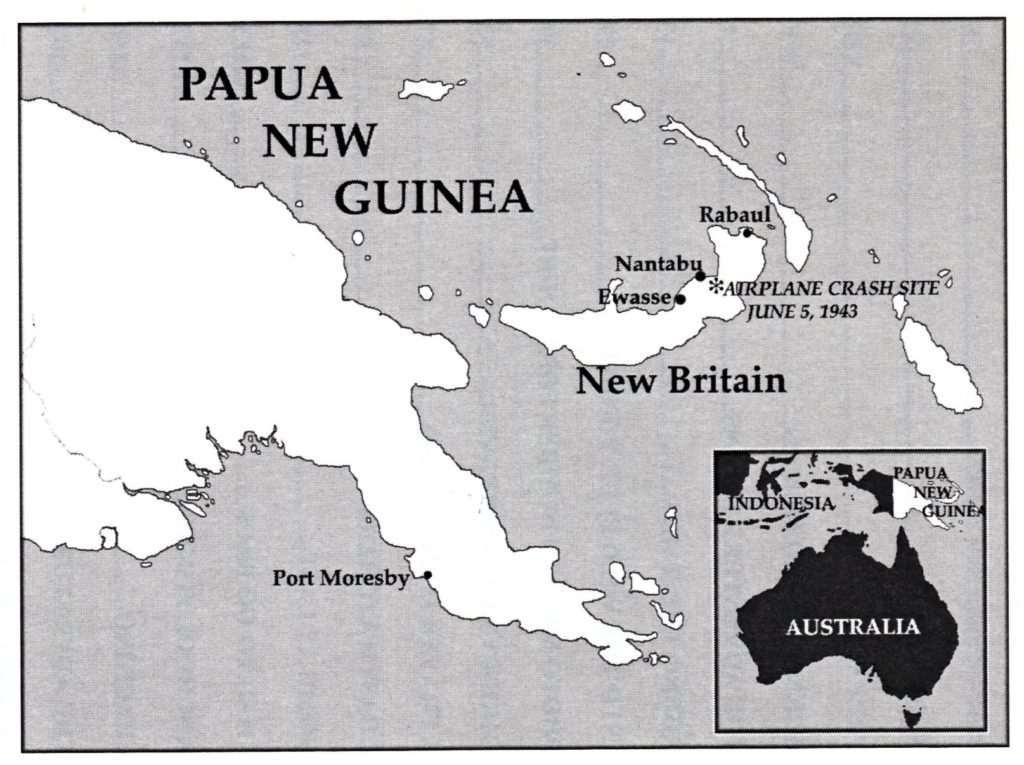

Very few people will have heard of The Airmen’s Memorial Primary School at Ewasse Village, in the Bialla District, West New Britain, Papua New Guinea, but for the people of the Bialla District, wartime evader Fred Hergesheimer is a household name.

On Saturday 5th June 1943, Fred was on a photo reconnaissance patrol in a P-38, over the north coast of New Britain. The Japanese were building up their forces around the Island of Lolobau and photo intelligence was an urgent requirement to allow the B-25s to do their job.

While photographing what appeared to be a Japanese airfield Fred’s P-38, known as ‘Eager Beaver’, was attacked by a Japanese fighter. A parachute descent was his only option and, after crashing through eucalyptus trees, he landed in mud. He had a nasty head wound so he crushed sulphanilamide tablets and sprinkled them on to the wound, then used pieces of parachute silk as a pad and applied a bandage to hold the lot in place.

Armed with his issued survival kit, and a booklet called ‘Friendly Fruits and Vegetables’, Fred wished that he had actually read the literature and listened to the survival briefings, as he took stock of the situation. He estimated that seventy five miles of thick jungle and two hundred miles of open sea lay between him and his base. There were no paths to follow and a vast wall of foliage to conquer but, with a compass in his hand, he set a course for the mainland.

By July 6th, after a month in the jungle, Fred had lost a lot of weight. He had been living on leaves, roots, snails and fish, looked like a scarecrow with a beard, was tired, hungry and felt very much alone. However, for Fred, July 6th, was a day that would pass into history, not just for him but also for the local people who encountered him. While searching for roots alongside a river, Fred heard voices. He froze. He had been spotted by some locals in a canoe. Moving cautiously, he walked toward the canoe, stumbling on a rock. With a warm sympathetic smile the leader caught Fred’s arm and saved him from falling.

At very great risk to themselves, the men decided to assist, feed, and hide Fred. He was given food and shelter for the night then, next morning, taken by canoe to their village. On arrival at the village of Ae Ae (later Nantabu) a bed was made up for him in the hut of the family of Luluai Lauo. Fred was acutely aware that to be caught in the village by the Japanese would mean beheading for him, and equally barbaric deaths for the local population.

For ten days Fred suffered badly from malaria, fever, and profuse sweating, during which time the villagers continued to watch over him and nurse him. Luluai was taken off for questioning by the Japanese on a regular basis and during that period Fred was often hidden in a mangrove swamp. When finally able to walk around the village he was always followed by school children whose job it was to rub out his footprints. Later, a group of hostile natives led a Japanese patrol to the village to search for the airman, but despite threats of execution and beatings, no member of the village, including the children, ‘knew anything about any airman’!

Then came a visit to the village by a member of another tribe who wanted to pass a message to the airman. The visitor was viewed with suspicion, but the piece of paper was given to Fred who saw the name of a Capt Skinner, Coastwatchers. The Coastwatchers were a secret organisation operating in Japanese occupied territory, reporting back to Australia on the troop, sea, and air movements of the Japanese. They worked in very small teams carrying out sea and road watches, supported by local people and steering clear of any contact with the Japanese.

Fred was taken by canoe to be introduced to Capt Skinner, the first white man he had seen in over five months, and then spent the next three months working with the Coastwatchers. After this period a submarine, USS Gato, made contact with the Coastwatchers and arrived off-shore to collect Fred and two other evaders who had been collected in, to take them to Australia.

Fred never forgot the people who had saved his life and in 1960 he made a decision to return to the jungle village and its people, to express his gratitude. After many travel adventures he arrived at ‘his’ village of Nantabu in darkness. There was no jetty so the villagers paddled out in their canoes. The men stood ramrod straight wearing white laplaps which shone in the moonlight; all were wearing ties and WW2 medals that they had earned for their work with the Coastwatchers.

The canoes took Fred ashore to the beach where the villagers were singing hymns; as soon as he touched land they broke into ‘God Save The Queen’. This was only the first return visit, as Fred and his family made plans to repay the villagers for saving his life.

By 1963, Fred finalised his plans to build a school for the village, funding for which was raised by sponsors in America. The school was a tremendous success. Fred and his family stayed for four years to ensure that the school became a reality. It was not just the village which benefited from the school project, but the whole area. By 1970, the school had six grades and 200 students. By 1996 there were 500 students. Many of the initial students were unable to speak English, but like many of their successors they today have highly respected academic accomplishments. Papua New Guinea has its own university and the official name of Fred’s school is ‘The Airmen’s Memorial Primary School, West New Britain, Papua New Guinea’ – the unofficial name, often used locally, is ‘The School That Fell from the Sky’.

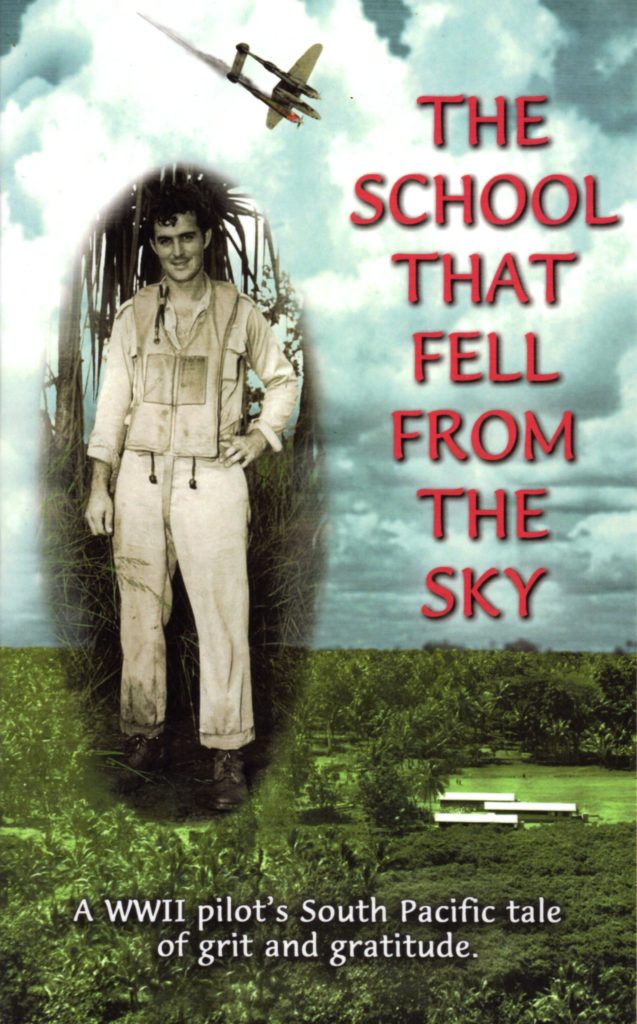

Fred Hargesheimer wrote about his adventures in his book, ‘The School that fell from the Sky’. The map at the beginning was taken from the book.