NEWSLETTER 4 – 2004

Roger Stanton

On the 11th October 1942, a number of evaders had gathered at a deserted villa at Canet Plage near Perpignan. They were waiting for a rendezvous [RV] with a fishing boat from Gibraltar. The Pat O’Leary Line had arranged the RV, and Pat was leading the men to the contact in darkness along the deserted beach. Standing alongside him was a tough Sergeant Major of the famous Canadian Regiment, The Fusiliers Mont-Royal. Armed with an iron bar, he was determined to deal with anyone who got in his way.

That man was Lucien Dumais; captured while serving with the Commandos on the raid at Dieppe, he had escaped from a POW train heading for Germany and had made his way south, mostly at night and alone, to Marseille, where he made contact with the Pat Line, and waited to be extracted from France via Gibraltar. On his return to England Dumais requested Special Duties, and asked to be returned to France to assist the escape lines. He was turned down by MI9 and returned to operations in North Africa, receiving praise for his work operating behind enemy lines. Back again in England he once more applied for Special Duties and the escape lines.

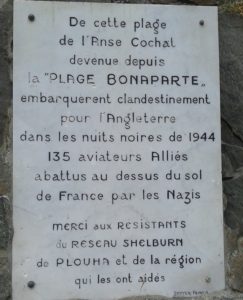

MI9 realised their previous error of judgement and enlisted Dumais to return to France where he created a very efficient escape line that enabled 135 men to return to England by sea, more than 100 were sent via Spain and Gibraltar, and over 80 were sent to the Forest of Freteval. Over 315 men were rescued in eight months by the Shelburn Line.

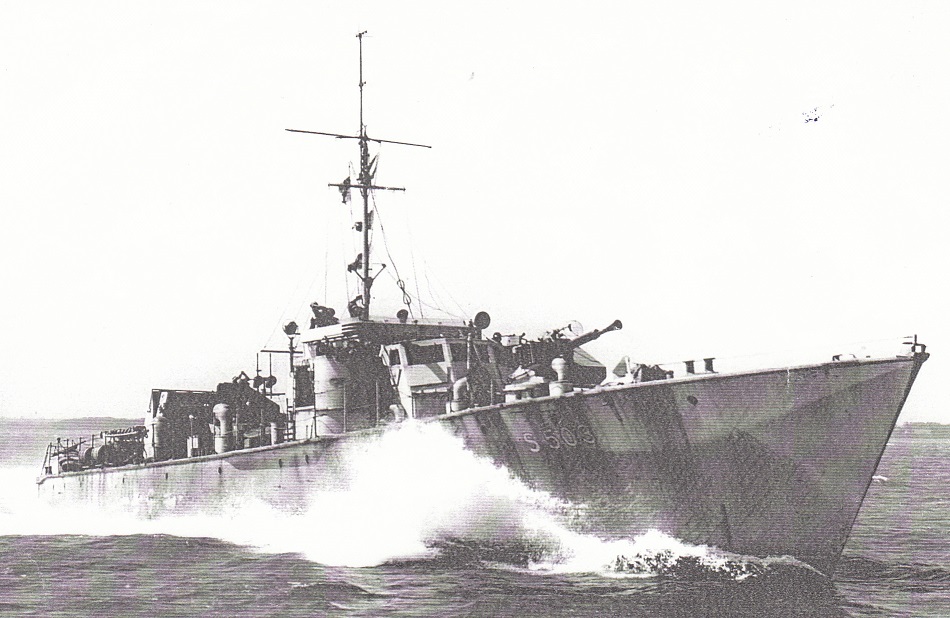

In February 1943, a previous attempt to set up a line in Brittany, called ‘Oaktree’, had been closed down quickly due to infiltration by the Gestapo; it had experienced problems from the beginning. In November 1943, Dumais and his radio operator Ray Labrosse, were taken to France in a double pick-up operation by two Lysanders from 161 Special Duties Squadron, piloted by Sqn Ldr Verity and Flg Officer McCairns. They landed WNW of Soissons then returned to base with a Belgian and five evaders. Dumais’ role was to set up an escape line from the Brittany Peninsular to Dartmouth. Ray Labrosse was taking an exceptional risk. He had already escaped from the Gestapo once, linked up with a party of evaders, had taken them south, crossed the Pyrenees and returned to England. The new plan involved crossings by the Royal Navy Gun Boats of the 15th Flotilla, mainly from Dartmouth, to RV with the Shelburn Line at a deserted beach near Plouha (code name Bonaparte) to collect evaders. By December 1943 Dumais had safe-houses arranged throughout the Plouha and Brittany area, with a main holding area in Paris. Couriers had been recruited throughout Northern France, this work being mainly carried out by girls and young women. Dumais then signalled London that he was ready to go.

On the 28 January 1944, in rough seas, eighteen men were taken off the small isolated beach near Plouha and returned to England. From the debriefing of evaders it immediately became clear to MI9 in London that the new line was very well organised, extremely thorough in its preparation and planning and, above all, was very security minded. Dumais had demanded a mine detector, which was used on every pickup to check the beach. Once found, a white handkerchief was placed over the mine, to be recovered on the courier’s return journey. On most occasions small dinghies were used to ferry the men from the beach to the MGBs, which waited about a mile off-shore. On the 28 February a second operation took place, 21 men were returned.

Although normally couriers led only two or three evaders at a time, Shelburn sometimes moved up to 24 evaders together in one vehicle. They were often masqueraded as Polish workmen returning from working on the Atlantic wall, given picks and shovels and coached in a sentence or two of Polish to mutter if stopped. Shelburn considered that one evader could be considered suspicious, but 24 in the back of a wagon was plausible. Also, the rationale was that if caught with a single evader the helper would certainly be tortured and shot, and if caught with 24 evaders they would still be shot, so it was worth the risk.

Many more evacuations by sea took place during the Spring and Summer of 1944. At the same time, some evaders were also taken south to the Pyrenees by Shelburn’s network of couriers, then over the mountains, and on to Gibraltar. Later in the summer, evaders were taken to the Forest of Freteval, near Cloyes, where they were hidden until liberation by the Allies.

Most operators from London stayed in the field for a maximum period of six months, before being recalled for a rest period. When Lucien and Ray were recalled they both refused to leave. The line was working well under their leadership, evaders were moving, and they considered that it was their duty to see the job through.

In common with other lines, Shelburn suffered attempted infiltration by traitors and collaborators posing as evaders, but none were successful. Roger le Legionnaire, who had been responsible for many deaths on the Pat Line, and Comète, was sent by the Gestapo to operate in northern France

using the name Roger Le Neveu, and ordered to infiltrate Shelburn. Fortunately his identity was realised before he could effect any damage. He was followed and his car was booby-trapped. Unfortunately a friend had borrowed his car that day, and twenty metres from the garage the car exploded killing the occupant. Although not killed, Roger le Neveu was not seen again in Brittany. He was later caught and dealt with by the Maquis at the end of the war.

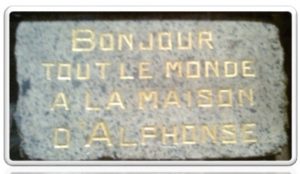

The Shelburn Line was ran on rigid, military security lines. It is believed that not one single evader was lost to the Germans once they had reached the hands of Shelburn. Also, although there were many compromising situations, not a single safe-house keeper or courier was captured by the Gestapo. The last safe-house on the line was ‘La Maison d’Alphonse’. A cliff top fisherman’s cottage, approximately half a mile from the beach pick-up point. The BBC ‘messages personnel, Ici Londres’ always broadcast a message to Shelburn before a collection. Usually twice during the evening, and often on the nine o’clock news. Confirmation of a collection was the coded message ‘Bonjour tout le monde a la Maison d’Alphonse’.

Captain Lucien A Dumais MC MM, died in Montreal, Canada, on the 10 June 1993, aged 88.