Edith Cavell 1885 – 1915

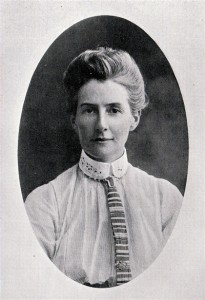

In 1865, in the small village of Swardeston in Norfolk, a lady was born who later was to influence many people on both sides of the channel, particularly Belgium. Edith Louisa Cavell was born in a Georgian farmhouse amidst the rolling farmland of Norfolk, where her father was curate of the village of East Carlton. No one at this early date could ever have imagined that her death would be mourned by the whole of the British nation together with many in Belgium, or that Queen Alexandra would have attended her funeral in Westminister Abbey. After attending The High School for girls in Norwich, and boarding schools in Peterborough, Bristol, and Kensington, Edith developed a strong interest in nursing. After several years as a governess Edith accepted a post in Brussels where she stayed for five years. In 1895, she returned to Norfolk to nurse her father through illness. In 1896 Edith began training at the London Hospital and was paid £10 a year, later moving to St Pancras, a Poor Law Institute for Destitutes, and in 1903 she became assistant Matron at Shoreditch Infirmary.

In 1865, in the small village of Swardeston in Norfolk, a lady was born who later was to influence many people on both sides of the channel, particularly Belgium. Edith Louisa Cavell was born in a Georgian farmhouse amidst the rolling farmland of Norfolk, where her father was curate of the village of East Carlton. No one at this early date could ever have imagined that her death would be mourned by the whole of the British nation together with many in Belgium, or that Queen Alexandra would have attended her funeral in Westminister Abbey. After attending The High School for girls in Norwich, and boarding schools in Peterborough, Bristol, and Kensington, Edith developed a strong interest in nursing. After several years as a governess Edith accepted a post in Brussels where she stayed for five years. In 1895, she returned to Norfolk to nurse her father through illness. In 1896 Edith began training at the London Hospital and was paid £10 a year, later moving to St Pancras, a Poor Law Institute for Destitutes, and in 1903 she became assistant Matron at Shoreditch Infirmary.

In 1907, Edith returned to the City she loved, Brussels, where she was put in charge of training nurses. Her father died in 1910 and while back in Norfolk visiting her mother in 1914, news of war came. Edith quickly returned to Brussels. On arrival back in the city, she was immediately caught up in the war. Both the French and British armies – withdrawing from Mons – were cut off by the German advance. Two British evaders from the Cheshire Regiment found their way to Nurse Cavell’s training School and were given food and shelter. Many more followed and an escape line began to emerge between Brussels and Holland.

Main organisers of the line were the Prince and Princess de Croy and Phillipe Baucq. For their own safety Edith kept the line secret from her nurses, as it was common practice for the German army to shoot people assisting British soldiers. After a year in operation two members of the line were arrested. Five days later Edith was also arrested and interned in St Gilles Prison in Brussels. Her nurses were very upset and visited her taking roses to remind her of Norfolk and England. During her questioning Edith Cavell admitted her guilt in assisting escapers.

During her trial Edith remained calm and dignified throughout and despite many pleas in  her defence, she and four other helpers on the line were sentenced to be executed at the Belgian National Rifle Range, the Tir National in Brussels. On her final morning, October 12th 1915, she rose at five o’clock. When the British Chaplain, Stirling Gahan came to see her, Edith spoke to him in a manner that summed up her character, “But this I would say, standing as I do in view of God and eternity, I realize that patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness to anyone”. He left the prison deeply moved. ‘I came to comfort her, and she gave me comfort’ he said on leaving. When asked for any last request, Edith requested large safety pins to fasten her skirt around her legs so that she could die with dignity. At 0700 the death sentence had been carried out. It is thought that many of the German soldiers fired wide and that a Private Rammel, when ordered to fire, refused and was himself executed. Edith Cavell was executed together with her fellow helper Phillippe Baucq. The grave of Pte Rammel was later found in 1919 between Edith Cavell and Phillipe Baucq.

her defence, she and four other helpers on the line were sentenced to be executed at the Belgian National Rifle Range, the Tir National in Brussels. On her final morning, October 12th 1915, she rose at five o’clock. When the British Chaplain, Stirling Gahan came to see her, Edith spoke to him in a manner that summed up her character, “But this I would say, standing as I do in view of God and eternity, I realize that patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness to anyone”. He left the prison deeply moved. ‘I came to comfort her, and she gave me comfort’ he said on leaving. When asked for any last request, Edith requested large safety pins to fasten her skirt around her legs so that she could die with dignity. At 0700 the death sentence had been carried out. It is thought that many of the German soldiers fired wide and that a Private Rammel, when ordered to fire, refused and was himself executed. Edith Cavell was executed together with her fellow helper Phillippe Baucq. The grave of Pte Rammel was later found in 1919 between Edith Cavell and Phillipe Baucq.

On May 15th 1919, Edith Cavell’s remains were returned to England for a ceremony at Westminster Abbey attended by Queen Alexandra and the Princess Victoria. At her family’s request, the coffin was then taken back to her beloved Norfolk where she was laid to rest outside Norfolk Cathedral – at Life’s Green.

Edith Cavell described herself as just a nurse, but to over 200 escapers and evaders whose lives she saved in one year, she was the heroine of Brussels from Norfolk.

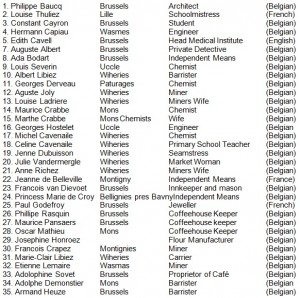

There were 35 members of Edith Cavell’s helpers initially arrested, listed as follows by the German authorities:

All of the above were arrested by the Germans between Jul/Sept 1915 and charged with conveying soldiers to the enemy. The HQ of the line at the Chateau de Bellignies, in the Forest of Bellignies, was also blown.

In 1939, Mlle Marie-Madeline Bihet, held the same position as Edith Cavell had in 1915. In 1940, Bihet and her nurses were once again hiding evaders. In the dark days of 1940, many of the nurses that Edith Cavell had trained in the nursing school were again assisting British soldiers in Brussels. They remembered Nurse Cavell, the English nurse and she became an inspiration to them all. As the war progressed other similarities appeared. Many of the Comete Line couriers were also trained nurses. St Gilles Prison again had cells full with members from the Comete Line. The Tir National was again in use as a place of execution, and on the 20th October 1943, Comete had its worst tragedy. Twenty-eight years after Edith Cavell’s execution, nearly to the day; one man was executed on the 17th and ten executed on the 20th October. Their crime? Assisting allied escapers and evaders. Many others similarities with Comete were apparent: like those arrested in 1915 many were from Brussels; many also came from the mining town of Wiheries with a very small population; once again the helpers came from all strata of life. Five were sentenced to death, others were sentenced to varying degrees of hard labour and eight were released. Only two were executed.

Near Trafalgar Square in London stands the large Memorial to Edith Cavell. Sadly, it is hardly noticed by passers-by, its most frequent visitors today are pigeons. It is however visited by ELMS for a short remembrance and wreath laying service in December each year.

Near Trafalgar Square in London stands the large Memorial to Edith Cavell. Sadly, it is hardly noticed by passers-by, its most frequent visitors today are pigeons. It is however visited by ELMS for a short remembrance and wreath laying service in December each year.