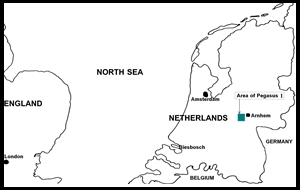

This item is not intended to provide a wealth of details on events in the Netherlands during WW2, but simply a general overview of what happened. The simple map shows the relative location of England and Holland as it was often called. (The provinces of North and South Holland form the western part of the whole country of The Netherlands).

This item is not intended to provide a wealth of details on events in the Netherlands during WW2, but simply a general overview of what happened. The simple map shows the relative location of England and Holland as it was often called. (The provinces of North and South Holland form the western part of the whole country of The Netherlands).

The history of Escape Lines in the Netherlands is more complex and fragmented than those in Belgium or France, for two principal reasons. First, during WW2 the Netherlands were controlled by the German SS, not the German Army, as was the case with most of the rest of Western Europe. Life in The Netherlands was much more controlled and rules more rigidly enforced than was perhaps the case in other western occupied countries. Secondly, assistance provided to evaders in the Netherlands was much more of a local affair and, with the exception of John Weidner’s Dutch-Paris Line, no one specific group organised an evasion route through Belgium and France. Many groups forwarded evaders to the Comete and O’Leary Lines. We should note also, that there was a high concentration of German military units in the Netherlands, as this area formed one of the key groupings of their anti-aircraft defence system because many of Bomber Command’s aircraft over-flew the Netherlands on their way to Germany; German fighters/night fighters were also based on local Dutch airfields.

For most escapers and evaders in occupied Europe, freedom usually meant heading south and crossing the Pyrenees into Spain, a distance of over 800 miles through territory controlled by the Germans who were often assisted by local police and militia, which made the journey very dangerous. Much of the journey had to be done by train, bicycle, or on foot. Records show that only three evaders escaped by boat across the North Sea from the Netherlands.

The location that an aircrew evader crashed or landed (usually by parachute) in the Netherlands, decided the nature of the help that he would be given, if any. Other evaders were brought down over Germany and speedily made their way to the border areas. Many local people were bullied and intimidated by the occupying forces and threatened with severe reprisals for assisting Allied aircrew. Consequently a number of evaders were handed over to the authorities.

There was significant activity by the German Counter Intelligence Services, the Abwehr, who employed ‘Double Agents’ with considerable success. These agents were responsible for infiltrating both the SOE section and many of the helper groups, resulting in some of the helper groups being compromised and agents, who parachuted into the country, being captured on landing.

Many helpers were executed or sent to concentration camps. Evaders who had been given assistance were quickly moved on to other organisations in Belgium and France. An example is the role played by Karst Smit and his group based in the Hilvarenbeek area, a small village to the south of Tilburg and quite close to the Belgian border. Smit collected evaders and passed them over the border into Belgium. Another group was run by Petrus Sijmons and operated from 1943 – 1944 in the Maastricht area.

Throughout WW2 there were numerous organisations in the Netherlands that gave help and assistance to Allied escapers and evaders; many were interconnected with other lines that were operational in Belgium and France. The longest and most independent line was deemed to be Dutch-Paris, which was believed to have been established in early 1943 as an escape line, when an RAF airman arrived in Paris and in a reply to a question ‘Where did you come from?’, he replied, ‘Dutch to Paris’. Before that date the line had no name and Dutch helpers were moving evaders into France, Switzerland and down to the Pyrenees.

The Dutch-Paris route was started by John Weidner, who spent many of his earlier years studying at Collognes on the French / Swiss border. He had walked extensively in his youth, and knew the border areas extremely well. With like minded friends Jacques Rens, Edward Chait, Jef Lejeune, Heerman Latsman, Paul Veerman, Benno Nykerk, Hans Wisbrun, and Father aan de Stegge, he set up a route from the Netherlands, through France, and into Switzerland. Many of the early couriers were known only to the evaders by their code names of Francoise, Okkie, Anne-Marie, Lucy, Simone, and Jaqueline. Although the route was successful, evaders arriving in Switzerland were then interned for the duration of the war and could not leave the country because of Swiss neutrality: so for some, their next task was to escape from Switzerland.

The Dutch-Paris route was started by John Weidner, who spent many of his earlier years studying at Collognes on the French / Swiss border. He had walked extensively in his youth, and knew the border areas extremely well. With like minded friends Jacques Rens, Edward Chait, Jef Lejeune, Heerman Latsman, Paul Veerman, Benno Nykerk, Hans Wisbrun, and Father aan de Stegge, he set up a route from the Netherlands, through France, and into Switzerland. Many of the early couriers were known only to the evaders by their code names of Francoise, Okkie, Anne-Marie, Lucy, Simone, and Jaqueline. Although the route was successful, evaders arriving in Switzerland were then interned for the duration of the war and could not leave the country because of Swiss neutrality: so for some, their next task was to escape from Switzerland.

A second route was then considered, with a ‘holding area’ of safe-houses in Toulouse, and other starting points to cross the Pyrenees based on Foix and St Girons. Many of the routes organised passed through Andorra. Other evaders were handed over to the Francoise Line in Toulouse. The route then continued on to Gibraltar, often via Madrid and Lisbon. The Pyrenees were extremely dangerous. The lower levels and routes were heavily guarded on both the French and Spanish sides, and the hated French Millice had infiltrated many of the local communities. The route itself was very difficult so experienced mountain guides were needed to guide fugitives over the high mountain terrain which was extremely hostile, requiring evaders to negotiate steep and rocky climbs over 9000ft [ in ordinary clothing and footwear and with none of the equipment that we would consider essential today]. Snow and blizzards prevailed for much of the year. The route, although difficult and hazardous, proved to be a success. In most cases the enemy did not wish to patrol the high routes. Regrettably, many evaders and guides died on these treacherous routes.

As more aircrew headed for the Pyrenees money became a major problem. The line was already paying mountain guides; more safe-houses were organised and evaders needed feeding; French helpers were already suffering under the rationing, so much of the food had to be bought on the ‘Black Market’. Rail fares, from Holland to the Pyrenees, had to be paid for, also the journey onwards to Gibraltar. Sponsorship from influential and wealthy Dutch supporters did not supply sufficient funding. Radio contact was made with London and support requested from the Dutch Government in Exile. The money was provided, to support both evaders and Dutch fugitives. The numbers of evaders being moved increased.

It is not clear at this stage how many evaders were moved by the Dutch-Paris Line, although indications are that the figure was over 1000, which included over 200 aircrew. One of them was Flt Lt van der Stock; one of only three evaders to make a ‘Home-Run’ after the Great Escape from Stalag Luft III. He reached Madrid and was then passed on to Gibraltar.

The flight paths of many of the nightly bombing raids took the bomber aircraft through a corridor over Belgium and Holland, and many aircraft were brought down over northern France, The Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg, resulting in many downed aircrew seeking help in those countries. Help was in many cases readily available, with evaders staying in safe houses until a place was available to go down an escape line. Some were moved to Brussels and continued via the Comete Line. Other routes led to the Pat O’Leary Line.

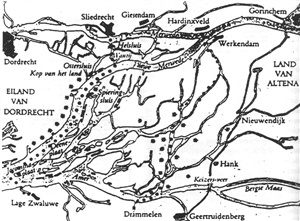

The escape groups in the Netherlands were highly organised. Many existed, but they often worked alone. The Biesboch area, a fresh water delta region of waterways, creeks and islands was a natural hiding place for evaders. Operations from the Biesboch resulted in large numbers of evaders, particularly aircrew, returning to Allied lines.

It is fitting, that today in the Lage Zwaluwe area is the large memorial statue of a Resistant/Helper (The Line Crossing Memorial). It commemorates the Dutch Line Crossers who broke through the front line 374 times with evaders and other fugitives.

As with all escape lines the Dutch had many problems. The price of freedom was high. Many couriers and safe-house keepers were lost. In one incident alone, a young girl courier was arrested in Paris with an address book in her handbag. Not all on her lists were working for Dutch-Paris, but 150 people were arrested and 40 died, or never returned from the concentration camps. One of those was John Weidner’s sister. Dutch historians indicate that about 1500 evaders were given assistance through the Netherlands. Over 400 were recovered from safe-houses on liberation, and a further 350 escaped from Operation Market Garden. The remainder were aircrew evaders.

After the Normandy landings on the 06 June 1944, movement of evaders in Holland became very difficult. The Allies were attacking railways, bridges and tunnels along the main communication and supply routes. After a short time Dutch-Paris suspended its route to the central Pyrenees so evaders were placed in safe-houses until overrun by the Allies, or until the helpers could take them through the lines to the Allies. Later as the Allied advance continued through Belgium and into Holland, Operation Market Garden took place on 17 September 1944. The objective of 1 Airborne Division, together with the Polish Parachute Brigade was the bridge over the Rhine at Arnhem. To add to the Dutch problems of hiding aircrew evaders, a new breed of escapers and evaders came on the scene – paratroopers from the 1 Airborne Division. The Division fought hard but had many problems to overcome, eventually having to breakout from the cauldron of Arnhem. The SS Division at Arnhem placed it on record that they had never fought a tougher enemy. Many broke out of the perimeter and were hidden by the Dutch people. Many were badly wounded. Many others, evading capture, were gathered in by Dutch civilians and taken through to Allied lines.

One Resistance man in the area, Fekko Ebbens, gathered in evaders [many sent by a Mrs Kok (Moeke) in Maurik and used his house as a ‘transit camp’. From the house evaders were taken to a crossing point at Tiel. These crossings were co-ordinated by a Capt King (a Belgian officer) of the British SAS Regiment. Also, at night, Dutch members of the Knokploegen (Dutch underground) had a crossing of the Waal organised for evaders.

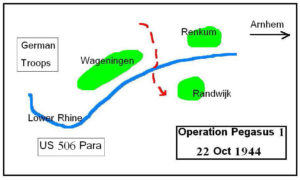

These successful crossings led Major Airey Neave (MI9) to consider large-scale river crossings for airborne escapers. The first proposed operation was given the name ‘Windmill’ and permission was granted by Col Jimmy Langley (MI9) to go ahead with the planning. At the same time Major Neave was also working alongside Major Fraser (SAS) to set up another escape route ‘Operation Pegasus’. Pegasus was to lead over 100 airborne soldiers to the Allied lines by crossing the Rhine. Two other men co-ordinating the routes were Capt Peter Baker (MI9) and an American Pte Ted Bachenheimer (a German of Jewish origin) from the 82 Airborne Division. Both men had been taken across the Rhine on the night of 12 October 1944. [Operation Pegasus was planned for 21 October.] On the 18 October, a Dutch resistant crossed the Waal and reported to Neave that Baker and Bachenheimer had been arrested and shot by the Germans. The courier went back to Tiel, but returned the next night with the news that the men had been arrested, but not shot; the Germans had found their uniforms and, it was thought, they were now treating the men as prisoners of war. Col Langley ordered Neave to cancel plans for Operation Windmill and concentrate on Pegasus, delaying the operation for 24hrs.

Lt Col David Dobie, had been sent across the Rhine on the 15 October to coordinate the operation with Dick Kragt, who was coordinating the Dutch side of the operations. ‘Operation Pegasus 1’ took place on the night of the 22/23 October. 138 escapers, mainly British Airborne, together with a number of Dutch Resistant’s were led to the Rhine. ‘Markers’ were laid out through the woods by men of the Glider Pilot Regiment; a bridgehead had been set up on the north bank by men of the US 506 Parachute Regiment; British and Canadian Engineers supplied the boats. Red tracer was used to mark the route to the south bank.

Based on the success of Pegasus I, a second operation Pegasus II, took place on the night of 17 November 1944. This operation was however compromised from the start and did not succeed.

The numbers of evaders may seem small compared with the numbers on operations throughout Europe, but the effect on morale when these men did return home was enormous. The thought that even if ‘brought down’, you still had a good chance of not only avoiding capture but also of making it home, was one that gave confidence to many. There is no doubting the bravery and selflessness of the Dutch people who participated in Helper activities, risking their lives for men they did not know. It is impossible to give accurate figures, but historians estimate that for every two evaders who made a ‘home-run’ to England, one Dutch helper died. Many suffered in the concentration camps for their courageous acts.

More information is available from ELMS – use the Contact Form to get in touch

http://weidnerfoundation.org/en/index.php/home/ – The John Weidner Foundation

http://dutchparisblog.com/ – Megan Korman’s research for the Weidner Foundation

http://wwii-netherlands-escape-lines.com/ – Bruce Bolinger’s research site

www.biesboschmuseum.nl – The Biesbosch Museum