Spain and the Escape Lines

As in all wars, an occupier needs the assistance of natural barriers such as sea boundaries, mountain barriers and waterways to protect his territory. The Second World War was no exception to this concept.

During WW2, possibly the most sought out route to escape from occupied Europe was to

head south and take on the challenge of the Pyrenees. Hostile, dangerous, and well guarded, the Pyrenees were not for the faint-hearted. Guides, suitable footwear and clothing were all essential and over the higher routes adequate shelter was a matter of life and death. In order to reach Gibraltar, the ‘Jewel-in-the-Crown’ final objective for many evaders, a trusted and well-organised route was essential. However, having made the crossing of the Pyrenees, problems of a different nature began for the escapers and evaders.

head south and take on the challenge of the Pyrenees. Hostile, dangerous, and well guarded, the Pyrenees were not for the faint-hearted. Guides, suitable footwear and clothing were all essential and over the higher routes adequate shelter was a matter of life and death. In order to reach Gibraltar, the ‘Jewel-in-the-Crown’ final objective for many evaders, a trusted and well-organised route was essential. However, having made the crossing of the Pyrenees, problems of a different nature began for the escapers and evaders.

Although deemed to be neutral, Spain hosted members of the Gestapo together with their own infrastructure of offices and headquarters. Evaders who passed through Spain also faced the possibility of capture by the Spanish authorities and internment in prisons in Lerida, Barcelona, Figueras, Zaragoza, Sort, and many others, prior to reaching the concentration camp of Miranda del Ebro. The camp at Miranda was overcrowded, and filthy. The prisoners lived in deplorable conditions and depending upon the speed that the British Consul was able to work for their release, prisoners could be held there for months. Under International Law, if the prisoners could prove that they were escapers, not evaders, they were often released. Evaders were to remain interned until the end of the war. The word soon spread back to England that, if captured, evaders were to proclaim that they were escapers from Germany!

Indications are that over 30,000 Allied troops passed covertly through Spain,  many heading for North Africa. In one month alone, 93 evaders arrived in Gibraltar. Donald Darling [code-named ‘Sunday’] was a contact point for the early escapers and evaders who arrived in Gibraltar. He was responsible for debriefing / interrogating them on arrival, and often used his flat on Main Street as a safe-house.

many heading for North Africa. In one month alone, 93 evaders arrived in Gibraltar. Donald Darling [code-named ‘Sunday’] was a contact point for the early escapers and evaders who arrived in Gibraltar. He was responsible for debriefing / interrogating them on arrival, and often used his flat on Main Street as a safe-house.

Initially the escape line [later to become the Pat O’Leary Line] was based on Marseille and organised by Capt Fitch, Capt Murchie, Lt Sillar, F/Lt Treacy, and later by Capt Ian Garrow. Garrow and Darling worked together despite the strain on the diplomatic organisation in Spain, which under Ambassador Samuel Hoare was determined that Spanish neutrality should prevail and did not want the British Government’s position compromised. Axis use of Spanish territory would have resulted in the loss of Gibraltar, Allied access to the Mediterranean theatre and the South Atlantic.

Other organisations such as SOE and SIS also operated through Spain. There was not one single escape line over the Pyrenees; all lines that headed south through France headed for that mountain range. For security reasons, each had different routes and used different mountain guides and couriers. At a later date an additional danger arose; should a fugitive be caught within 5km of the border area they would be handed back to the French authorities. Garrow initially organised the mountain guides but later, when compromised, he had to follow his own route out of France leaving the line in the hands of Albert Guerisse [Pat O’Leary]. At the end of 1942 the Germans took over the unoccupied zone of France effectively closing the sea evasions from Canet Plage that had been run by O’Leary, so forcing more evaders to the central Pyrenees. Later, in early 1943, Marseille was compromised and most of the key players on the line, including Pat O’Leary, captured.

The O’Leary line moved inland to be based on Francoise Dissart’s home in Toulouse. Francoise rebuilt the line, renaming it the Francoise Line. She hired new mountain guides and chose higher, more difficult routes for evaders in the belief that they were less likely to be patrolled by the Germans. Most followed smugglers’ routes, some of which headed for Andorra. The starting point became the area around St Girons.

The O’Leary line moved inland to be based on Francoise Dissart’s home in Toulouse. Francoise rebuilt the line, renaming it the Francoise Line. She hired new mountain guides and chose higher, more difficult routes for evaders in the belief that they were less likely to be patrolled by the Germans. Most followed smugglers’ routes, some of which headed for Andorra. The starting point became the area around St Girons.

According to the escape records of individual escapers and evaders, it appears that some of them were led over the Pyrenees by guides from the areas of St Girons or Foix, but most were led by Spanish, Basque or Catalan guides. Throughout southern France and the French border areas many Spanish Republican exiles formed the backbone of the SOE-supplied Maquis groups. Most took part in attacks on German military concentrations until the end of the war.

Key to the successful transportation of escapers and evaders from the border areas was the covert assistance of the British Diplomatic Service. The Consulate at Figueras was of great help to the O’Leary Line before it became compromised in Marseille. The Consulate at Bilbao supported the Comete Line that started in Brussels and followed a westerly route to the area of Bayonne and St Jean de Luz before crossing the hills and the River Bidassoa. On reaching Spain, the evaders were often collected by a diplomatic car driven by British Consulate official Michael Cresswell. Sometimes fugitives were moved by train using documents provided by the British Embassy, although they were more often ferried between diplomatic locations and into Gibraltar hidden in the boot of official diplomatic cars.

Many of the escape lines throughout Europe ended their routes in Spain where they were supported not only by the covert actions of the British Diplomatic staff and their communities, but also by the safe-house keepers of the border areas. It is also without doubt that MI9 provided much assistance to the operations in Spain.

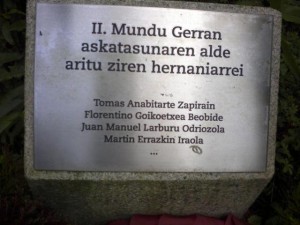

The present Spanish Government is keen to “recover” its history. For example the Catalan government recently opened a museum at the site of the old prison at Sort in Catalunya (where many escapers and evaders were held) to mark the end of the Chemin de la Liberté. At the same time the French in St Girons opened a similar museum at the beginning of the Chemin de la Liberté. Officials from both towns took part in each other’s ceremonies, demonstrating the importance being attached locally to commemorating the Escape Lines. In the Spanish Basque country the town council of Hernani, the birthplace of Florentino Goikoetxea, have erected a memorial to four local Basque guides associated with the Comete Line – Tomas Anabitarte Zapirain, Florentino Goikoetxea Beobide, Juan Manuel Larburu Odriozda, and Martin Errazkin Iraola.

The present Spanish Government is keen to “recover” its history. For example the Catalan government recently opened a museum at the site of the old prison at Sort in Catalunya (where many escapers and evaders were held) to mark the end of the Chemin de la Liberté. At the same time the French in St Girons opened a similar museum at the beginning of the Chemin de la Liberté. Officials from both towns took part in each other’s ceremonies, demonstrating the importance being attached locally to commemorating the Escape Lines. In the Spanish Basque country the town council of Hernani, the birthplace of Florentino Goikoetxea, have erected a memorial to four local Basque guides associated with the Comete Line – Tomas Anabitarte Zapirain, Florentino Goikoetxea Beobide, Juan Manuel Larburu Odriozda, and Martin Errazkin Iraola.