I WAS THERE – DRIVER LES LAWS DCM – ROYAL ENGINEERS

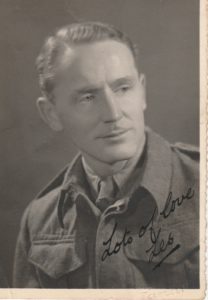

Les Laws DCM

[From Les Laws’ memoirs, with the permission of his daughter, Patricia Palmer]

This story is an unusual one, and to some degree, unique. It is an escape story in which some 81 Allied escapees from a German POW camp played a role and suffered some considerable ordeals, in which luck played a major part, and in which one life was lost. A story that took four years to unfold, starting on a beach in Greece and ending in a POW reception depot in England.

As 2195978 Driver Les Laws, I sat on the beach, and as daylight approached, the last of the Naval Destroyers covering the evacuation from Greece disappeared into the gloom. Far too tired to care much about what was going to happen, I then fell asleep – and that is all I can remember until a jack-booted leg awakened me the following morning, 29th April 1941 shouting, ‘Auf, auf’.

My tale from then, until June 1944, is just the same as many other prisoners of war; long forced marches, weary train journeys in cattle or cargo tucks on the railways of Greece, Austria and Yugoslavia, indifferent and sometimes brutal treatment, work and more work, with an occasionally happy thought of home or a Red Cross parcel. Eventually I had been moved to Stalag XV111A, at Wolfsberg, Austria, and then to a work camp, some 150 miles away at Maribor in Slovenia, near to the Yugoslavian/Austrian border. Maribor was a communication centre and rail marshalling yard of some significance.

It was also a main communications centre for the road and rail network in the greater area. We were employed on track maintenance. I was attached as the official German interpreter, which gave me a special standing with my captors, one of which was to get on tea making duties and speak with local people. I had escaped four times before, but had been caught on each occasion resulting in a spells in solitary on bread and water. The difficulty was not the escape itself, but getting away afterwards through the difficult wooded and mountainous terrain. The works party carried out track maintenance 18 miles from Maribor. Each morning some 80 POWs were herded into a train with 18 armed guards in the early hours of the morning and taken to the work site and then returned to the main camp at night. The Yugoslavians were also in the work camp and gave updates on war news and local gossip. Tito and his Partisans were gaining considerable strength and were a thorn in the side of the occupying armies. On tea making tasks I visited homes and had to wait for the water to boil, and at the same time I spoke with the local people. A regular home I visited was that of Lisa Zavodnik with her two children who chatted in passable German. In conversation I also heard that the Partisans were active ‘just over the mountain’ from where we worked and that a large group of Partisans were based in a village on the other side. ‘Over the mountain’ was very vague, but it was tempting to consider the possibility of escape. The information I kept to myself, and in the next four days I managed to get food parcels out of the work camp and hidden in shrubbery. There had been no successful escape attempts before, as there was nowhere to escape to! The guards were not friendly, but not domineering. One day on a visit to Lisa’s house for hot water Lisa looked very uncomfortable and tense. The answer came when a door from the kitchen opened and in walked three men. A very menacing sight. All had sten guns, grenades were around their belts, and their uniform was different. We conversed in broken German. They were interested in the camp and the strength of the camp guard. After a few minutes they had gone. That was my first contact with the Partisans.

As time moved on, rumours that Partisan activity was ‘just over the mountain’ grew stronger and I decided to attempt an escape. In mid-June ‘44, I discussed my plans with others: Ralph Churches who was camp leader and Kit Carson – both Australians; a Scot, Andy Hamilton; a Londoner Len Austin known as ‘Eggy’, who was able to obtain eggs for the camp from sources only he knew; and two New Zealanders Bob McKenzie and Griff Rendall. Initially, only Ralph Churches was keen on the idea, but later the others came round. An escape plan was arranged and they stored their food parcels too. We decided to go soonest: during the following morning we would all pay visits to the wooded area at different times, collect our food parcels and meet up; we would then travel through heavily wooded areas into the hills and try to contact the Partisans. At 0930 the next morning, 22 August, I strolled into the woods for ‘a call of nature’ and, at intervals, the others followed my lead. Although the going was very rough, and slow at times, we headed in the right direction. We knew the best we could hope for was an eight hour start, before the men were checked back on to the train. Although we had not informed other prisoners of our plan, they had worked it out. As they were counted on to the train, the first seven slipped out of the other side, walked down the track, got under the train and re-joined the line to ensure the count was correct – we were not missed.

During the afternoon we crossed the mountains, some at about 4000ft, and headed down into the valley. The Partisans controlled the country but German patrol posts were spotted. By late afternoon 15 miles had been covered and we had passed through the enemy patrol base areas. When darkness fell, we came upon a village. An old lady was spotted; I spoke to her in German asking for the council chambers, she pointed, and we moved on. Outside the building were two guards in khaki, not grey, uniforms. They were Tito’s Partisans. We were taken to see the local commander and after explanations we were taken to the Commanding Officer – aged 20, with the rank of Major. We were interrogated again and our identity accepted. We were in the village of St Lorenzon, and taken to the Officers’ Mess for a good meal, given accommodation, and greeted by other local people who had worked on the railway and recognised us. That night, to celebrate our escape, the whole village turned out and a dance was held in our honour, windows were open, loud music played, lights were on. This was proof that the Partisans held the area.

The following day I spoke with the CO and suggested to him the possibility of returning to the scene of our escape, attacking the guards, and releasing the rest of the prisoners. He was delighted with the idea. By 0200hrs, Ralph Churches and I, with 20 Partisans, had passed through the German line again and reached the railway cutting where we crouched down to await the arrival of the POW train. It arrived, the men got off and started to collect their tools when a howling group of Partisans charged into the guards and, without a shot being fired, had taken them all prisoner. I then grouped all the POWs together and explained the plan to get them back to the British Lines. Not all agreed, but after a few harsh words from Ralph Churches and myself they agreed. Then, with our German prisoners, we started back over the mountain. We returned to St Lorenzon and found that another ten prisoners had also been released, and nine French prisoners from a neighbouring farm. The French were reluctant to join up with us but after harsh words they did. We then continued on over the next mountain. By evening the German prisoners were stripped of their outer clothing, boots and socks and then set free to find their own way back home. Keeping to the rule of fifteen paces between each man, the column was now several hundred metres long.

The column of marching men continued through the sparsely populated hill and mountain areas before reaching the HQ of the 14th Div. of the Partisan National Liberation Army. Names and numbers were transmitted to the British Army HQ in Italy, on radios dropped to the British SOE mission who worked with the Partisans in the area. Many volunteers joining the Partisans reported here; one man was found to be a traitor and caught putting arsenic into the soup – under the Partisan’s strict disciplinary code he was placed under close arrest. On the same day, another Partisan had received news that his wife and daughter had been arrested by the Germans as a result of him enlisting; to him this meant a final destination for them – a concentration camp. Heartrendingly, he walked to the edge of the clearing, sat on a log, rested his chin on his rifle and fired. We buried all that was left of him.

The Commanding Officer organised for us to move on the next day. He explained he could only spare a guide and two guards. He needed his men to fight diversionary actions to keep the German troops away from the line-of-march of the POWs and other Yugoslavs. The party was 160 strong, with male and female civilian volunteers. The rules were to maintain single file at 15 pace intervals through enemy territory until we reached Tito’s HQ. The CO informed me that it would be difficult, but I was to ensure that everyone got through safely! It turned out to be an extremely gruelling journey – continuous movement with only occasional 2 hour breaks for meals, but never more than four hours rest in 24 hrs. The routes followed mountains, heavily wooded slopes and areas, lonely but friendly farmsteads. After four days, and by now completely exhausted, we reached a farmstead. Our armed guard approached carefully looking for signs of German occupation. Once it had been cleared, a meal was prepared and we settled down in a hay-filled barn for a well-deserved sleep. Regrettably during the rest stop our prisoner escaped.

We moved on and at about midnight, still in single file, we were crossing a ridge when a burst of machine gun and small arms fire greeted us. The leading Partisan was killed and everyone else scattered and regrouped about a mile back. The escape of our prisoner had brought its retribution. We had lost one of our two armed guards – killed – and six POWs were missing. Our guide took over and led us silently around the back of the German positions some fifty yards away. We were so close we could hear the enemy talking in undertones. We continued on for another eight days, walking for up to 20 hours a day. One of the main obstacles was the wide Sava River, a tributary of the Danube, which had to be crossed. It was too deep to wade and nearly 500 yards wide where we had grouped. Fortunately the Partisans had worked a plan with the local farmers; they had to get their horses and carts over the river at harvest time to collect grain and the Germans had agreed horse-crossings to enable a full day’s work in the fields. Two crossing points were chosen, about 300 yards apart. We moved in silence to the chosen point. Suddenly, at 2200hrs an enormous crashing sound was heard and four large draught-horses pulling carts charged down the slope and into the water. The din was deafening as they crossed the rocky beach and into the river. Between the two crossing points for the horses and carts, two men in rowing boats ferried everyone across, not more than six at a time. All together more than 240 people crossed. During the crossing, gun fire was heard some distance away where the Partisans were fighting diversionary actions. Everyone got across without problems. The Partisans Intelligence network was, without doubt, very good. The enemy had occupied the country but did not control the ground. They rarely took on the Partisans at night or on their own ground.

On reaching the far bank we again started walking. On the 12th day we reached Cemic, a town occupied by Partisans and only a short distance from Tito’s headquarters. The Yugoslav contingent left us, to go and enlist into the Partisan army, and we were temporarily billeted in a school. Everyone’s feet were blistered, swollen and raw. We stayed there for a week to recover, during which time four of our lost POWs were brought in by Partisans, and we met Captain Sangers, a British Officer serving with the SOE mission attached to Tito’s Partisan forces, who explained that it would be necessary to find a suitable landing strip for Allied aircraft to evacuate us to Italy. At the end of the week we undertook a three-hour march before spending two days preparing a new landing strip with the Partisans. [Four landing-grounds should have been available but three had been compromised.] The following afternoon we moved to the landing strip to await the RAF aircraft from Italy who were due at 2130hrs. At 2030hrs trouble started. The landing strip was attacked by Mahailovitch forces (a counter Partisan group who were in a private war with Tito’s Partisans and often worked with German forces). There were casualties on both sides, but fortunately no casualties amongst the POWs. The airstrip was rendered cratered and useless.

Two days later a different site had been located and a new airstrip prepared. After another two days we gathered at the new airstrip in early evening to see the truly glorious sight of six RAF Dakota aircraft circling the area. A parachuting figure leapt from one of the aircraft and landed on the airstrip. On his confirmation that the area was safe he signalled the aircraft to land. He was a British Naval Officer who was later awarded an MC. All six aircraft were quickly unloaded of the stores and ammunition destined for the Partisans, then wounded Partisans and 79 ex-POWs were boarded for evacuation. Five aircraft took off and landed at Bari in Italy. The sixth aircraft was grounded due to engine trouble until the next day, when another Dakota arrived with a fighter escort, landed with spares and an aircraft mechanic, and finally it took off with the remaining POWs to reach Bari in the afternoon.

At Bari the reception was less than welcome! Nobody knew about us! We waited on the airfield until trucks arrived to take us to a transit camp. Again we waited until moved to a rest camp north of Bari. During interrogations we gave details of the marshalling yards at Maribor, which the RAF later bombed, causing severe destruction to them and to the rail link we had worked on. We were again moved on to a rest camp at Salerno, where our Australian and New Zealander escapers left us for home. We then embarked on the SS Cape Town Castle and arrived at Liverpool on the 21 October ‘44. Nearly a year later, at a POW Reception Centre, I met the two ‘lost’ men. They had been recaptured. Of the 81 (+ 10 French) that escaped from Maribor 89 got through. Sadly one Partisan died, killed in the ambush. Twenty days after leaving the camp and after over 200 miles of difficult walking, we finally left Yugoslavia. Surely few stories can involve so many instances of good luck, yet it happened. It was the biggest mass breakout from an Allied POW camp in WW2 and would have not happened without the infra-structure, organisation and help of the Partisans.

_______________________

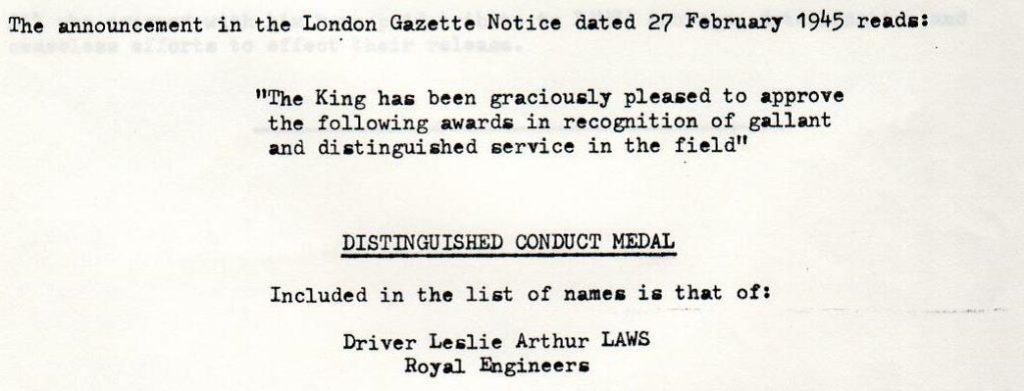

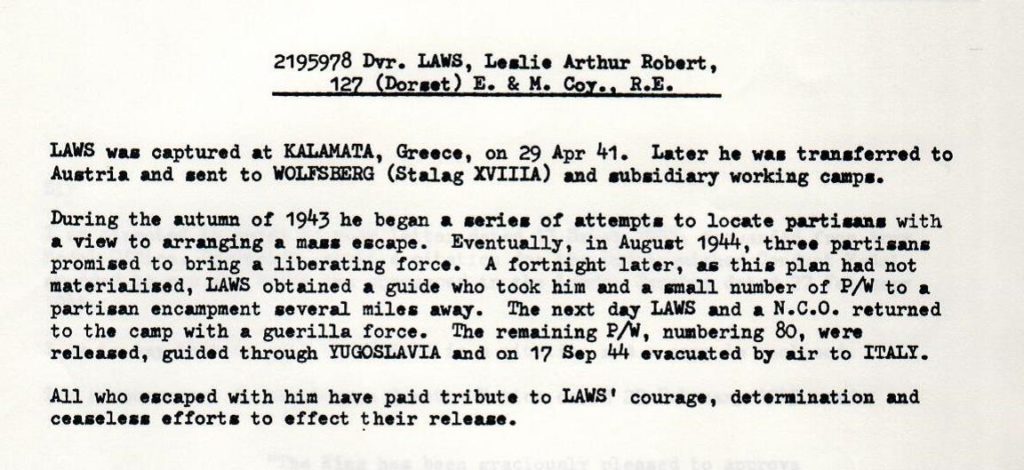

Les was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal [DCM] for his actions in Slovenia.

The London Gazette and the Citation read: