Pilot Officer Kevin McSweeney

P/O Kevin McSweeney was the pilot of Lancaster LL276 on the night of 22/23 May 1944. He and his crew were on a mission to Braunschweig in Germany. During the flight to the target they were attacked by a German night fighter, and the aircraft was set on fire. McSweeney ordered his crew to bale out but before he could escape the fire detonated the bomb in the bomb bay! The entire nose section, with McSweeney stiil in it was blown off. Remarkably, McSweeney survived the explosion practically unscathed and was able to deploy his parachute, landing safely close to the Dutch border. During his descent he saw two other parachutes before he landed. Once on the ground he buried his ‘chute and flying jacket and searched for other members of his crew. He was unable to locate anyone else so eventually set off westwards, towards the Netherlands.

P/O Kevin McSweeney was the pilot of Lancaster LL276 on the night of 22/23 May 1944. He and his crew were on a mission to Braunschweig in Germany. During the flight to the target they were attacked by a German night fighter, and the aircraft was set on fire. McSweeney ordered his crew to bale out but before he could escape the fire detonated the bomb in the bomb bay! The entire nose section, with McSweeney stiil in it was blown off. Remarkably, McSweeney survived the explosion practically unscathed and was able to deploy his parachute, landing safely close to the Dutch border. During his descent he saw two other parachutes before he landed. Once on the ground he buried his ‘chute and flying jacket and searched for other members of his crew. He was unable to locate anyone else so eventually set off westwards, towards the Netherlands.

As it turned out four of his crew were captured soon after landing, becoming prisoners of war for the duration. Two were killed, and were buried in a forest cemetery in Germany. They were a mix of Australians seconded to the RAF, and Englishmen. They were very close-knit, and the survivors remained life – long friends.

McSweeney reached the Dutch/German border and by taking note of the border patrol pattern he was able to cross from Germany in daylight. He eventually came across a Dutch shepherd in a field, but a group of peat diggers nearby started waving and beckoning and so he went over to them instead. He learned from them that the shepherd was a Nazi sympathiser. The diggers helped remove the insignia from his uniform and gave him directions. He spent three days walking, staying overnight in haysheds and getting food from Dutch farming families happy to help a “British” airman. On one occasion he was stopped by a German soldier on a bicycle, wanting directions. All he could do was say “I don’t understand” in English. Neither his words nor his RAF battle dress aroused the soldier’s suspicion – he just shook his head and rode on.

Later, another man on a bicycle rode past, stopped, turned around and spoke to him in English “Do you need help?”. McSweeney replied “Yes”. The man took him to the home of Johan Meewis, the leader of the local Dutch resistance. Apart from actively prosecuting a guerrilla war against the Nazis he organised the escape of downed aircrew, which involved moving them from one place to another accompanied by guides, or “couriers”, with the aim of getting them to one of the established escape routes to England.

Anneke, the young girl in the next photo, was one of his couriers. The young lady has a reason to hide her face. This photograph was taken in The Netherlands, World War II is raging, and she is a courier in the Dutch underground. The Gestapo shot such people with little ceremony.The man on the left of the photo is an American airman named Bill Weaks, from South Carolina. The other is Kevin McSweeney. He was just 20 years old and on his 18th mission when he was shot down.

His family no longer have the original WO telegram reporting him missing, but do have several that his mother sent to other family members; the first one simply said

KEV MISSING OVER GERMANY

The family heard nothing for several months and then came news that some of the crew had been captured. The family telegram read

4 KEVS CREW POW 2 UNKNOWN KILLED NO NEWS KEV

Meanwhile in the small town of Wijhe, a very small Dutch town, McSweeney was hiding in the mechanism room of the clock tower , where he spent three days while the room below was occupied by German army spotters, making use of one of the few high points in the flat Dutch landscape to look for downed airmen. They were looking in the wrong direction! A local boy, Jan Janssen, son of the local police chief, looked after him while in this cramped room. His father gave him a key to the tower. Each time the army spotters’ watch shift ended McSweeney crawled out from his cramped hiding place to stretch out in one of the German’s bunks.

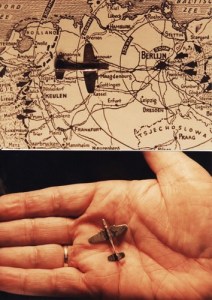

After a few days his ‘helpers’ decided it was time to move him another hiding place. The resistance used women and girls to guide downed allied airmen from one hiding place to another. It was a very dangerous business. Anneke escorted Dad by train to his new location, a small room in an apartment in Amsterdam, which he shared with Bill Weaks, the American. At this time stage of the war (June 1944) the Allied had just mounted their invasion of Normandy, and the situation in occupied countries was very difficult as the Germans reacted to the growing Allied presence in northern France. Movement of POWs became especially difficult, so the two airmen in the photo had to spend almost three weeks cooped up in hiding. McSweeney had been given some silver coins, and to relieve the boredom he melted them down and made little models of aeroplanes, about an inch long. His young courier, Anneke has one to this day as a most precious treasure, and had some photos of it taken for McSweeneys family.

The escape routes started moving again and so it was arranged for McSweeney to go to a certain house in Brussels, but this time his luck ran out. There was no one at home, and a neighbour suggested he go to the local cafe to wait. That neighbour was a collaborator. McSweeney was captured at the café and then taken to St Gilles prison, now run by the Nazis. It was used to hold a mixture of prisoners, including those suspected of being in the resistance, political prisoners, some allied airmen, common criminals and deserters from the German army. None of the prisoners were treated in accordance with the Geneva Convention.

According to McSweeney’s report there was a gruesome routine in this prison. Every morning a shot rang out. That shot signalled the execution of another prisoner. Perhaps it was the Nazis idea of a wake up call. McSweeney was there until the beginning of September 1944 and his experiences left him with two lifelong effects: Nightmares and dental problems caused by malnutrition.

By that time the allied advance into Europe was forcing the Germans back towards Germany, and the German High Command ordered the 1370 prisoners in St Gilles prison to be moved to Neuengamme concentration camp in Germany. However the local Belgian authorities were determined to prevent this, and with the assistance of the local railway staff did everything they could to delay and disrupt the movement of what was to become known as the ‘Ghost Train’. After the train moved a number of times around the Brussels area the German plan was eventually thwarted by the combined efforts of the railway staff and local resistance. The Germans eventually abandoned the train near Schaerbeek in north east Brussels and left the prisoners to their own devices . On the 3rd September McSweeney and two others managed to escape from the carriage holding the POWs and made a run for it, soon making contact with the advancing allied army eventually returning to England.

A final family telegram, four months after the first one simply read;

KEV IN ENGLAND PERFECTLY FIT

Though he didn’t need to, and it must have distressed his parents, McSweeney continued with flying – now as a Flight Lieutenant – and formed a new crew, but fortunately the war was over before he needed to fly another combat mission.

Postscript (by a member of the family)

It was only a span of a few years but a generation was defined in those years. What intrigues me most is the presence of a spirit in some people that will not bend to evil, while yet similar people in similar circumstances will. The shepherd who would have given Dad to the Nazis, while the peat diggers helped him. The people of the resistance on the one hand, and the collaborators on the other. In ordinary times one would have been hard pressed to tell them apart.

The bravery of people like Johannes Meewis, the Dutch underground leader. He went by the codename of Carl. After the war he was honoured by both the British and American governments for the help he gave to downed airmen, such as Dad. We have a copy of the citation from President Eisenhower. Tragically, his health suffered terribly from the stress and deprivation of these times, and he died in 1947. He was a hero of the highest order. There were many brave men and women amongst his colleagues – the “helpers”.

Kevin knew none of the real names of the Dutch helpers, nor was he told any addresses, for obvious security reasons. But those helpers knew his real name and some knew he was from Australia. They heard when he was captured by the Gestapo and, hearing nothing more, feared the worst. But they didn’t forget.

Jan Janssen, the young boy who had helped Kevin when he was hiding in the tower moved to the Dutch East Indies after the war. He happened to hear a program on Radio Australia about the trials of downed aircrew in Europe, in which Kevin’s name was mentioned, so he wrote to the station seeking to get a contact address. We have the letter sent by Radio Australia. Anneke and others from the Dutch underground obtained Dad’s address through the Red Cross. One of the peat diggers got in contact, as did the father of one of the other helpers.

Perhaps not too surprisingly, until she found Dad’s actual address in 1988, Anneke was under the impression that he was an American, and even tried advertising in the American Air Force magazine (we have a copy of the advert). When I found this out I was reminded of one of Dad’s stories from his trip by train across the US (on the way to England). After talking with a couple of girls in California, who had asked where they were from, Dad heard one note to the other “They speak English well, don’t they?”.

Have a look at the photo of Anneke with Kevin and Bill Weaks again. Soon after this was taken Anneke saw twelve of her friends rounded up and shot by the Gestapo, in one day. She still has nightmares about those times. She eventually travelled to Australia as a guest of the Royal Escaping Society (courtesy of KLM) and she stayed at our house for a while. Anneke and Kevin stayed up all night talking over those times. Perhaps it was for the best, but Dad was terribly shaken by the retelling of those experiences.

I will finish with an English translation of a poem that Anneke wrote about “Kevin Mac Swaney, American Pilot” – as she thought at the time – a few years after the war, not knowing whether he had survived or not:

“You were the warm sunshine

Which came through the window

The wind which sung through the trees

A song that could only be short.

You were the tender night music

The sky full of stars

The white moonlight on the ground

A melody full of romance.

Your mouth your laughter your eyes

So clear as the sparkling water

You could drink without worry

An arm around my shoulder.

Autumn on the silent beach

A wave that broke against the rocks

Your soft voice that speaks of love

Two white shells on the sand.

Love unsuspected

You were the yellow flower field

The summer that quickly ends

And spreads into Autumn nights.

You were my happiness in sorrow

My underground love song.”