Newsletter No43. – 2017

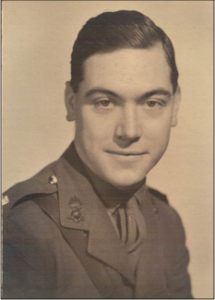

Captain Peter Baker – MC, Croix De Guerre, Savoy Cross, Medaglia D’Oro

WW2 took its toll on many of the nation’s soldiers when they returned home. Many were restless; mental problems claimed others; and some felt the need to return to the familiarity and security of army life and routine. Families who had anticipated ‘cosy reunions’ suffered, because in many cases it proved very difficult for their menfolk to adjust to a peacetime role, and the women who had been left at home found themselves bearing the brunt of adjustment – not only of the men, but of the confusion of their children reacquainting with their fathers.

WW2 took its toll on many of the nation’s soldiers when they returned home. Many were restless; mental problems claimed others; and some felt the need to return to the familiarity and security of army life and routine. Families who had anticipated ‘cosy reunions’ suffered, because in many cases it proved very difficult for their menfolk to adjust to a peacetime role, and the women who had been left at home found themselves bearing the brunt of adjustment – not only of the men, but of the confusion of their children reacquainting with their fathers.

Captain Peter Baker had a hectic war; he fought in all the campaigns in the Middle East and NW Europe, mostly behind enemy lines, with Phantom, the Resistance Groups and the Escape Lines. He worked with 2SAS and Popski’s Private

Army, MI9 and the Intelligence Corps. Sadly at the end of the war he was one of the many who found difficulty adjusting to a peace-time role. After an illustrious, action-packed wartime career, Baker, the civilian, proved to be one of the many peace time casualties of war. He formed and controlled 17 companies, employed 500 people and became an MP at 28. Regrettably his restless lifestyle resulted in health problems, a nervous breakdown and involvement in a dubious business venture. He died at the young age of 45. He was just one of the many casualties of the peace.

Born in Cricklewood in 1921. Educated at Eastbourne College, speaking both French and German, Peter Baker gained a place at Cambridge University, but due to the interruption of WW2 this was placed on hold, and he chose instead to join the Royal Artillery as a gunner five days before war was declared. He was offered a commission but insisted that he wanted to serve in the ranks first, so started off in the lowest rank in the Royal Artillery. After eight months he accepted a commission and went to the Officer Cadet Unit at Catterick Camp, passing out as a 2nd Lieutenant on 7th September 1940. He was posted to Home Defence and served in western Scotland. In October 1941, with life boring he agitated for change and was attached as a Lieutenant to the Intelligence Corps. He applied for a transfer to the Intelligence Corps, which he took up in the autumn of 1941. Within four months he asked for an active service posting overseas. In October 42 he was posted as an A/Captain to the GHQ Liaison Regiment known as Phantom as an Intelligence Officer.

Phantom, the code name of an unusual Regiment created in 1939 and disbanded in 1945, was secret and unorthodox in its methods. Its HQ Squadron was from the Royal Corps of Signals and its transport from Light Armoured Squadrons of the Royal Armoured Corps. It was comprised of many of life’s characters from various Regiments, RAF personnel, mobilised academics, members of Parliament, the nobility and even members of the criminal fraternity. The role of the Regiment was forward reconnaissance, passing through enemy lines and reporting back to the Commanders, by radio, details of the location and intentions of enemy units. Initially they were deployed to France with the BEF, then after destroying their vehicles

at Le Panne, near Dunkirk, they returned to England, re-grouped and later deployed to Greece and North Africa, where at one stage they were based at Giarabub, an oasis 200 miles south of Mersah Matruh. Nine patrols operated from this base on Intelligence gathering duties.

Following training in England and the mountains of Scotland (where he suffered a bad fall), Baker was posted to E Squadron of Phantom in Algeria, under the command of Major Hugh Fraser, working in North Africa with the First Army. [The three Squadrons (E, K and H) were deployed together with an Assault Unit.] Later the Squadron moved to Tunis as part of Hopkinson’s Force, with the SAS, 1 Airborne, and Popski’s Private Army to re-organise to follow the Assault Unit led by Christopher Mayhew on the invasion of Sicily. In August Sicily fell and Montgomery’s troops had crossed the straits from Messina, gaining a foot-hold on Italy in September.

Following Sicily, the Squadron was briefed for the invasion of Italy, where, once on the mainland, the Regiment’s role was to undertake long-range deep-penetration patrols into enemy territory. A forward base had been set up at Taranto, from where Baker, with a small team, operated with a lightly armed, unarmoured jeep up to 100 miles into enemy territory to locate enemy positions and movements. These were reported back to the forward base for further dissemination at operational briefings. In December 43 the Squadron moved to Trani, but just before Christmas, 1942, Baker became ill and was flown back to Britain for treatment.

While he was in England Baker was ‘head-hunted’ by MI9 and offered the command of a small Reconnaissance and Intelligence Section, part of the Intelligence School 9 (IS9), Western European Area (IS9 WEA). The unit had been formed by Airey Neave and Jimmy Langley who were both escapers and now at MI9 at Beaconsfield. Baker’s role was to run and re-organise escape routes in France and Belgium after D-Day. At the end of May he assembled his Section and landed on Juno Beach on D-Day+4. He found that the established escape routes were now compromised by the landings, and that many road and railway routes had been damaged by Allied bombing. He also identified potential problems for evaders and their helpers emanating from food shortages, roaming groups of SS, and the developing anger and aggression of the enemy due to the more overt activities of the Resistance. With a team of one officer and eight French members Baker managed to trawl in over 150 evaders (mainly air- crew) from the battle area, collection/holding points and safe-houses, and to return them to England.

With the breakout from Normandy the battle area had expanded. Evaders were now being sheltered in groups in forest areas as their onward movement was restricted by travel problems. Three locations were identified as ‘danger areas’ for evaders so MI9 established Operation Marathon, covering areas in France, Belgium and Holland, to rescue the inhabitants of the forest areas. The Operation included the establishment and administration of covert organised camps – ‘trawling in’ of stray evaders, sheltering, feeding, supplying, occupying and guarding, whilst remaining undiscovered – and the eventual extraction of the inhabitants. There was great risk for the men, the organisers and any rescue force. MI9 organised different Intelligence Sections; Special duties flights were detailed to extract aircrew evaders in Lysanders, Hudsons and Dakotas; and teams moved with battle groups on the front line to collect in evaders. Although IS9 (WEA) was part of the 21 Army Group under Field Marshal Montgomery, for security reasons the staff were give GSO staff jobs to hide their real activities and rarely went near 21AG. Being a very small and lightly armed unit, IS9 could do little to liberate the camps on their own, and most Allied units considered them a private army so preferred to give them a wide berth as they had their own objectives to meet.

Early in August, Baker and his section were moving to Rennes; after dropping off an American Section to head to Brittany, they continued on route following the US 3rd Army under General Patton. IS9 were preparing to liberate the Forest of Freteval under the Operation Sherwood plan. On arrival at Le Mans on the 10th August the Battle Group stopped and Neave set up IS9

headquarters in the Hotel Moderne. Now about 50 miles from Freteval, he toured the various US HQs to try to request men and transport to help liberate the camp. Despite his efforts, the Americans had other priorities on the battlefield and declined to help, stating that light tanks and infantry would be a necessary requirement as German tanks and troops were known to be in the area.

A disappointed Neave returned to Le Mans and sent out a section to seek out the local French Resistance to request transport for the rescue using civilian vehicles. Meanwhile he became aware that a ‘rather tough looking group’, who turned out to be a British 2SAS Squadron under Captain Anthony Greville–Bell, and who had completed their operation, were resting in Le Mans awaiting orders from London, and were now also resident in the Hotel Moderne, having parked all their heavily armed jeeps in the courtyard. That evening another Squadron comprising Belgians from 5SAS, arrived, together with their own radios. Greville-Bell contacted London and the next day received confirmation that both SAS Squadrons could liberate Freteval with Neave.

Maps were studied, routes chosen and, as it was not known who controlled the roads, it was decided that Capt Peter Baker should lead a recce and also explain to the men in the forest that they had to wait for organised liberation and not disperse. His team, with five SAS troops and their officer, left in jeeps, acquiring a motorbike along the way, and arrived in the early evening having been engaged in a fire-fight on route, in which one man was injured.

The next morning the Americans were again approached for vehicles, and again refused. Later, Neave was requested to head to the main square in Le Mans where he was confronted by members of the Resistance who had gathered sixteen coaches and trucks for the camp liberation. They left at speed the next morning, the SAS leading the way and covering the rear.

Passing through flag waving villages and towns on route they were delayed by welcome speeches and champagne, but they arrived at the camp and by afternoon they were back in Le Mans. The roll call of the camp was 152; 132 were collected by Neave’s party and another ten by the Americans. It was assumed that the remainder had left or headed for the villages. On the 14th August Baker volunteered to return to the camp with the SAS to try to find the missing airmen (only to discover that they had left with the Americans) and was caught up in a fire fight with the French Resistance – who thought they were Germans. No one was hurt.

Following this episode Baker moved on to Chartres to recover more airmen, and then on to Paris. Once again, as the SAS were occupied with their own operations, transport was requested from the Americans but again the request fell on deaf ears. The group split up, with Baker taking an infiltration route to Rambouillet, and Neave taking the other party to Dreux and then Auneuil where thirty two hidden airmen were rescued. Other rescues were considered in Paris, but without SAS assistance and the reluctance of the Americans to get involved, their journey was delayed. On the 26 August they arrived in Paris on the same day as General de Gaulle. They entered Paris, to the accompaniment of German sniper fire from windows. In Paris many evaders had walked to freedom and their helpers were celebrating. Moving north with the front line, the pace was so fast that when the Guards Armoured Division entered Brussels on 3 September, evaders were still hidden in safe-houses. The unit did not dwell in Brussels which had been liberated, and continued with the advancing front line to Holland.

A base was established in Eindhoven on the 18 September ‘44, and ‘forks’ went out to establish contacts with both the Dutch Resistance and the Escape Lines. The Dutch were very cautious because the German Operation ‘North Pole’, Englanderspiel, had caused devastation to SOE and its communication system in Holland, resulting in many deaths. Also, Holland had been administered by the SS and not the Wehrmacht, resulting in fear of continued bullying, terror, reprisals and betrayal. As a consequence, for security reasons many of the Resistance groups and Escape Lines did not share ‘information/intelligence’, but retained their separate identities and worked alone. Despite this Baker made contact with the Resistance groups and

was able to relay Information to London, together with details of the V2 rocket sites and the propellant used. Much of this information supplied by Baker was used to develop the Navaho rocket which, after many changes would lead to the missile systems we have today.

In October Neave and Baker moved their base to the west of Nijmegen. Baker crossed the line, by canoe over the River Waal, to recce the area and attempt to meet up with other Resistance groups. The canoe returned carrying the future Dutch Foreign Minister who was heading to London with important Intelligence. Baker remained behind the lines and managed to achieve co-operative working between some of the Resistance groups. On 13 October, he was guided to the De Wildt fruit farm, near Zoelen, run by the Ebbens family, and based himself at this house together with Theodore ‘Ted’ Bachenheimer, a 21 year old American Paratrooper who had crossed the Waal with him.

The house was risky due to its location on the line and the number of people sheltered. It was a transit camp for the Dutch Resistance and for Allied evaders. Fekko Ebbens also gave shelter to Dutch people escaping the Gestapo, and to Jews. Ration coupons and weapons were also stored at the farm. A Dutch member of the Abwehr, Johannes Jacobus Dolron, posing as a German deserter, infiltrated the line and reported back to his handlers. On the night of 16/17 October the house was raided by German troops. Fekko Ebbens and four Resistance were shot, and the farm was later burned down. Baker and Bachenheimer, thought to be SOE or spies, were taken for interrogation. Both insisted they were escaping POWs. They were arrested in sleepwear, but fortunately their uniforms were still in their bedroom and their story was believed. The men were taken firstly to a holding camp at Culemborg, then marched 45 miles to Amersfoort, and then on a 5 day train journey to Stalag X1-B at Bad Fallingbostel. During the journey Bachenheimer escaped. His body was found on the 23rdOctober at Met Harde, 25 miles north of Arnhem. He had been shot in the neck and in the back of his head. There is a memorial to him on the spot which includes the Star of David – Bachenheimer was a Jew and knew the danger of capture.

Baker delayed his escape attempt, but later joined up with a French, and a Belgian, soldier. On the 7th November 1944, they passed themselves off as a French work-party to collect firewood from the forest. On reaching the wood they ran off, heading west. They managed to cover forty miles before being caught by a German farmer with a shotgun and a dog and handed over to the local Volksturm. About to be taken to the Gestapo, Baker revealed his real identity. This was disbelieved, and the soldier raised his pistol to shoot Baker. They were only saved by the farmer, who protested that they could not be shot on his land and should be returned to the camp to be shot. Sent back to Stalag XB at Sandbostel Baker was brutally interrogated before being given 35 days solitary confinement and then moved to Oflag 79. He was put on trial for escaping and for forging a leave pass as a foreign worker; the Gestapo and prosecution wanted the death penalty but this was changed to six weeks in a penal camp, of which he only served twenty eight days – the camp was liberated by the Americans on the 12th April ‘45. After a talk with the US Forces Baker was given permission to make his own way home; he requisitioned a Mercedes and drove to Paderborn; flew to Ghent, then Prestwick and London. He weighed seven stone. On the 2nd August 1945, 148257, Capt Peter Baker of the Intelligence Corps was awarded the Military Cross in recognition of his gallant and distinguished services in NW Europe.

At the end of the war Baker’s military doctor ordered him to take six months off and to spend half of that time in bed to rebuild his emaciated body. He also suggested a number of surgical procedures that would be to Baker’s advantage and comfort. Baker would have none of it and headed for the business world. He entered Parliament at 28 and became an MP for the Conservative Party (1950); he won the seat again in 1951. Baker was a frequent visitor to many of the Gentleman’s Clubs in London, from where many of ‘Phantom’ had been recruited. In 1954 Baker suffered a nervous breakdown due to an excessive workload and had to enter a nursing home to recuperate. His business suffered financial problems and in 1954 the official receiver was called in.

Peter Baker died in St Mary’s hospital Eastbourne on 14 November 1966, aged 45. A man who had lived life to the full in all senses, always ‘on the edge’, and a victim of the costs of both war and peace.

Rog Stanton with edits by Rob Belk.